Chromophore

2023 (Photographic commission on the Nord-Pas-de-Calais Mining Basin)

Nature for man is only the “nature” in the human biotope, but nature itself exists independently of us. This nature is not the “nature” of human culture that makes sense to us, because it exists independently of human interests. That’s why, fascinated by this unknown nature, we’ve tried to approach and understand it, using mimicry and our imagination to embody it in a form we can possess. Color, in particular, has been considered as a symbol that replaces plants, animals and natural phenomena, and the primitive trichromaticism of black (charcoal and soot), white (bone and limestone) and red (iron oxide and red clay) has been used in witchcraft and rituals, due to its association with shamanism. Today’s color psychology also considers that red, yellow, green, and blue are the psychological origins of color, and that the color space of the human brain is formed by six colors: red, yellow, green, blue, light (white) and shades (black). In other words, the primary colors, and states of light, one of nature’s phenomena and the source of vital activity, are the origin of the colors we perceive.

As an example, in ancient Japan, which is surrounded by mountains and sea and has a closer relationship with nature than other countries, there were no words for colors such as red and blue, but they did try to express nature’s colors in terms of states of light, describing the glowing scarlet sky at sunrise as “明 (mei)”, the darkness after sunset as “暗 (an)”, the bright light of noon as “顕 (ken)” and the sky turning deep blue at sunset as “漠 (baku)”. Of course, there were many other colors than these four primary colors, but as most of these colors were extracted from plants and minerals, the materials themselves were used as color names, and memories of this practice are still present today in the names of pigments in Japanese painting. These natural colors also symbolized nature’s repeated births and deaths for the ancient Japanese, who therefore expressed their gratitude and respect by wearing matching colors for each season. In other words, they were trying to establish a link with nature by overlapping human life onto the transitions of nature, which gradually changed with the seasons, eventually fading and decomposing, and giving birth to new colors.

As industrialization and urbanization progressed, the once close relationship between man and nature became progressively more distant. The symbiosis between man and Satoyama*, an example of the preservation and use of nature, has been forgotten over time. As a result, we focused uniquely on the use of nature, exploiting it day and night, exhausting all resources, and destroying wildlife habitats. Today, there is no natural space without human intervention, and isolation is the only way to maintain primeval natural areas. However, due to atmospheric pollution and global warming, which are getting worse every year, even unspoiled nature, plants, and animals cannot escape human influence, and it is predicted that 15-20% of all species will become extinct by the end of the 21st century, including species that humans do not yet recognize as such. In addition to this, the effects of the destruction of nature, which were not clearly visible until now, have begun to affect human health in a more direct and shorter-term way, in the form of the transmission of zoonotic diseases, and new contagious diseases are likely to continue to increase in the future, unless actions are taken to re-establish the boundary between wildlife and man. Faced with this situation, and because everyone has experienced the pain of losing so much as a result of COVID-19, have we realized that the answer to protecting nature lies not only in cutting off the relationship between nature (isolation), but also in reconsidering the way in which it could be used? With these ideas in mind, I wonder if it’s possible to build a Satoyama-type relationship between terrils and us…

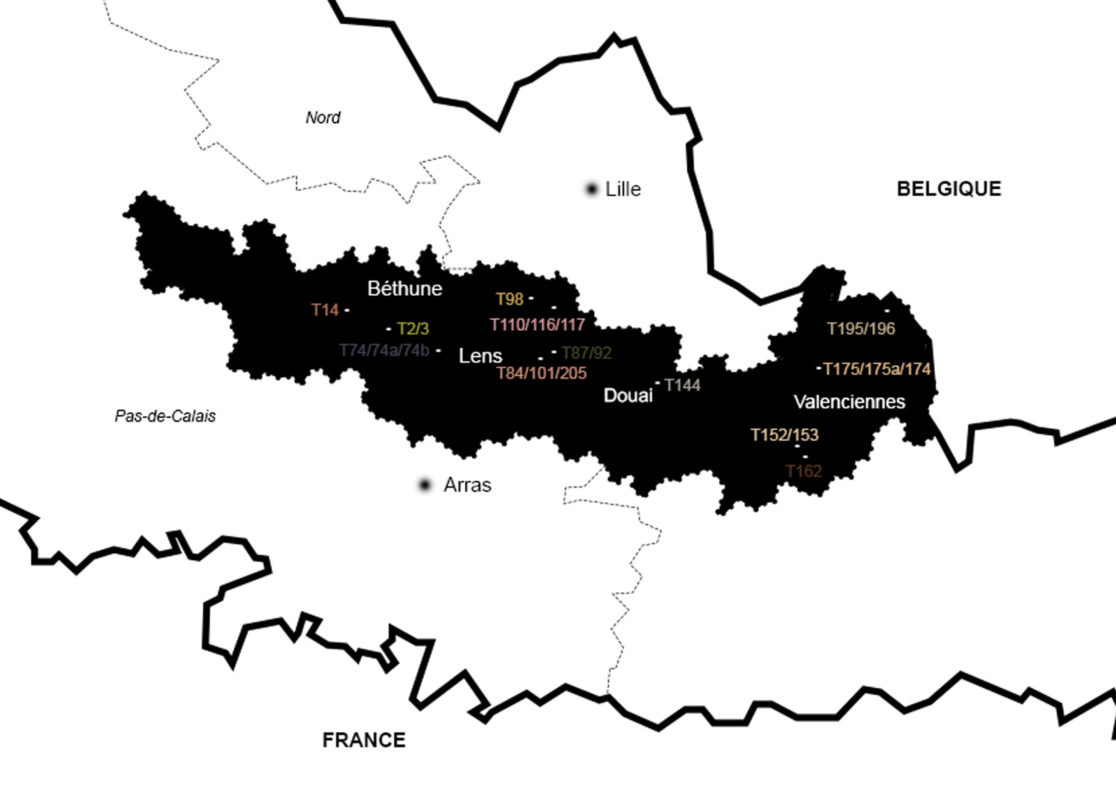

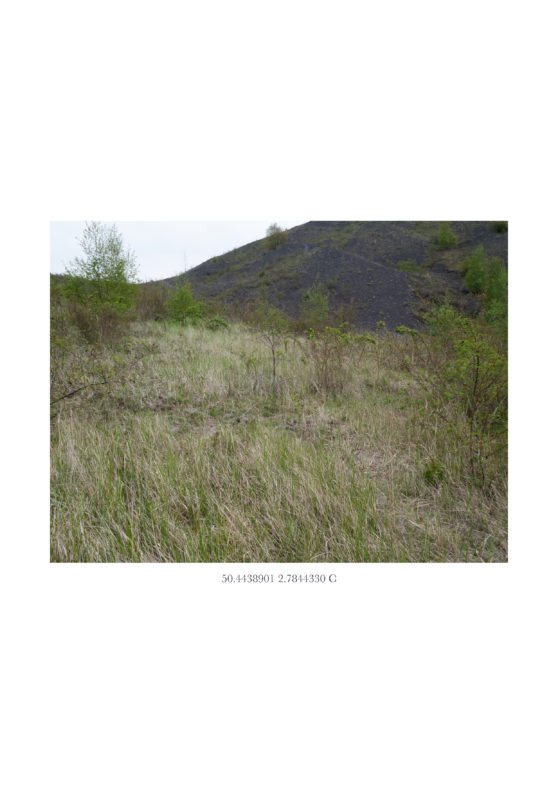

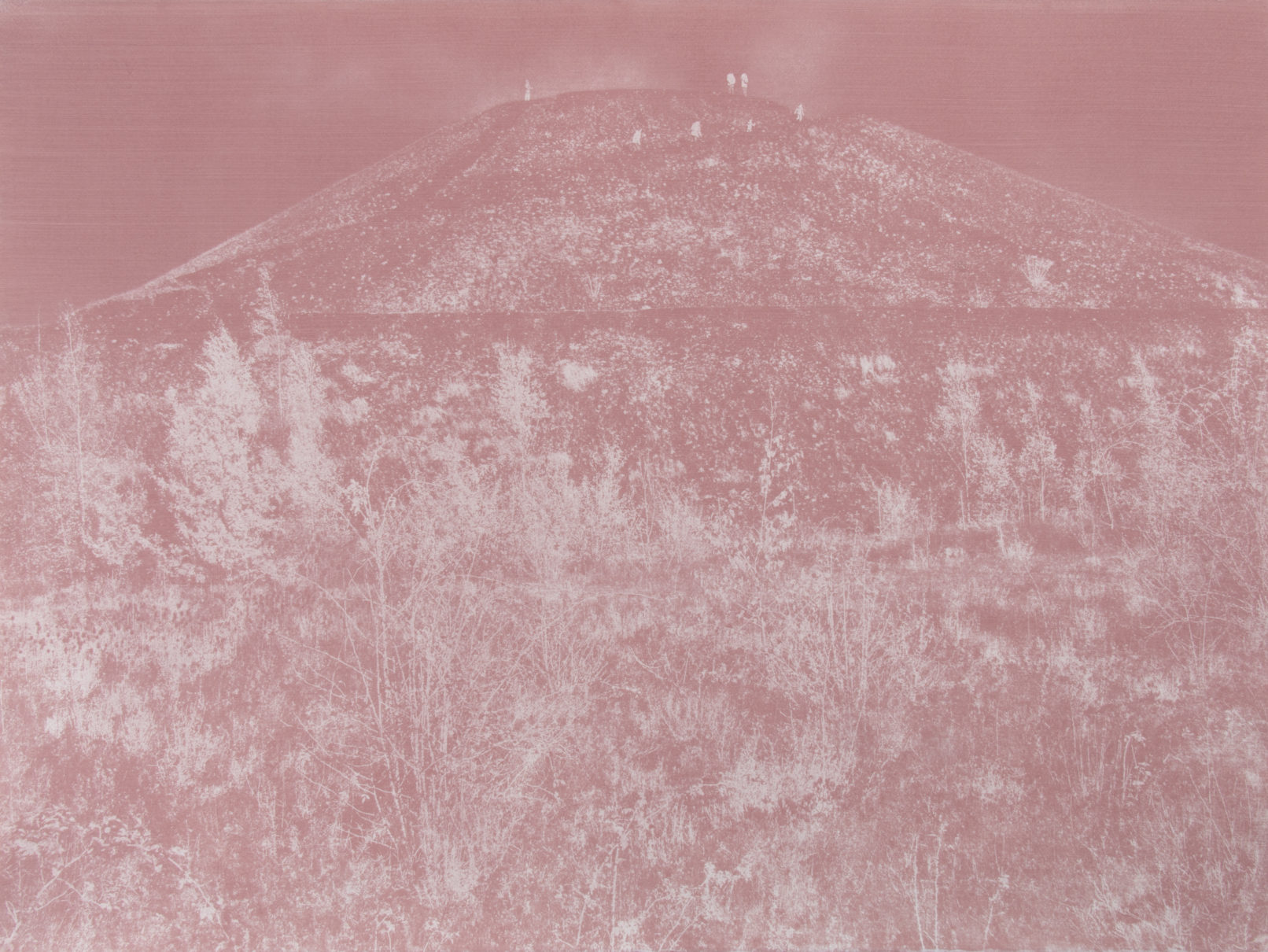

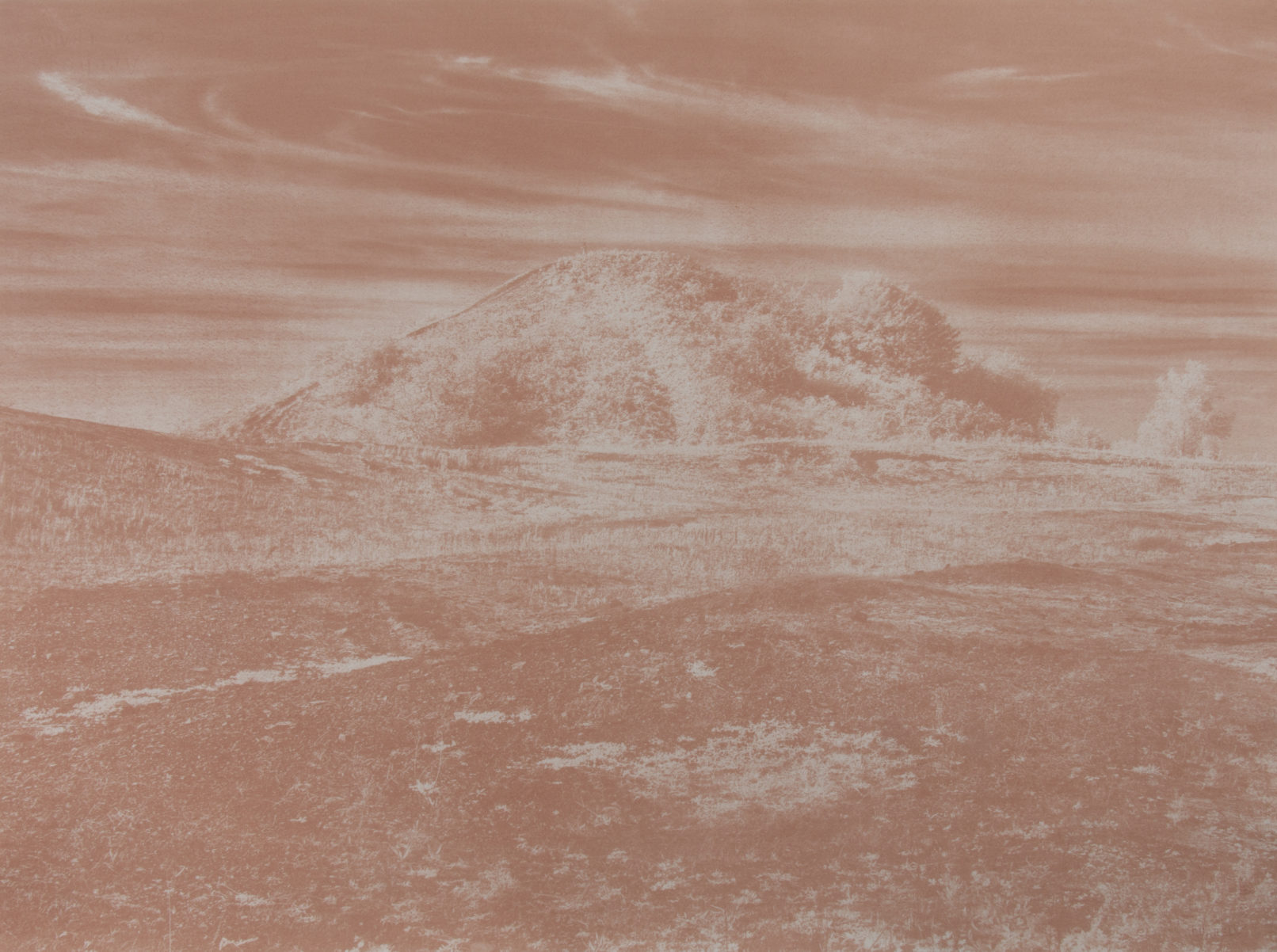

The first time I saw a Terril* was from the window of a high-speed train as it approached the North of France after departing Paris Gare du Nord. I had just moved from Japan, and I remember being awestruck by this strange black mountain that suddenly appeared in the flowing scenery. I immediately needed to know more about it. This particular black mountain was that of Terril de Sainte Henriette in Hénin-Beaumont; one of what I would soon find out is a vast network of 200 or so man-made mountains stretching from the border of Belgium west throughout the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of France. When I first visited this terril, it was snowing. The tall monochromatic contrast of pure white snow against the dull black remains of coal symbolized a mountain filled with countless memories of the people involved.

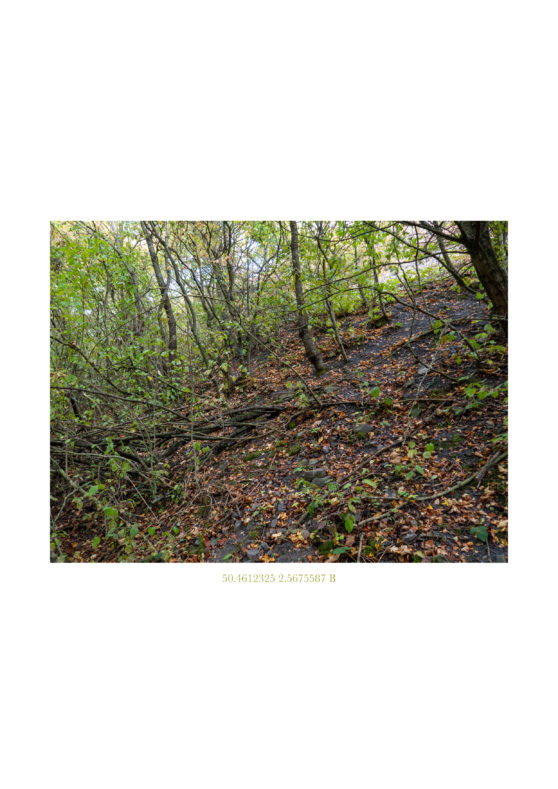

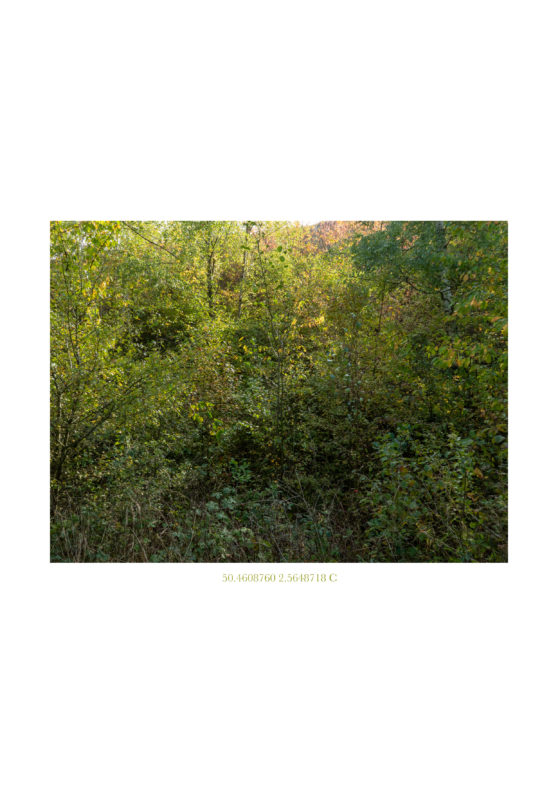

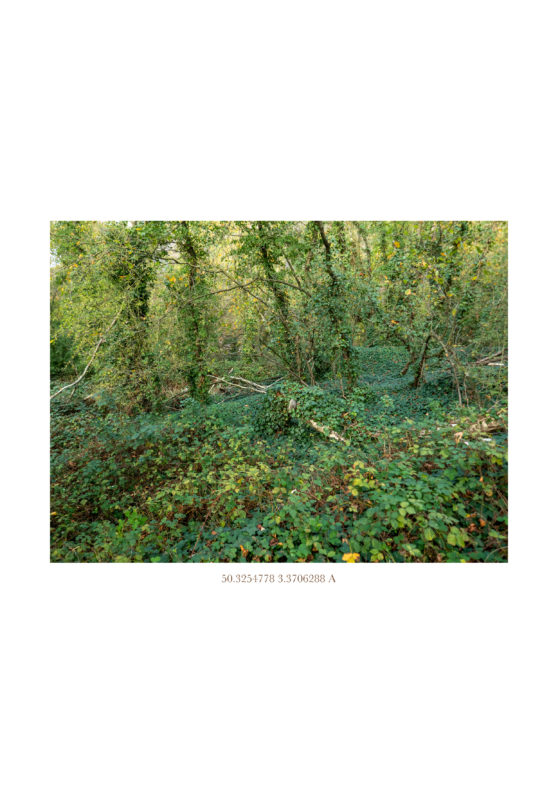

Today, 11 years later, I find myself once again facing the terril. The slopes, which once seemed all black, are now covered with wildflowers such as Yellow horned poppy and Reseda lutea, and against the clear skies of early summer, it’s filled with a palette of varied colors, in the opposite of the monotony of winter. Not only to examine the archives, but also to understand in real terms the differences between each terril through a dialogue with each site, I visited terrils of different shapes and periods spread across the Nord-Pas-de-Calais Mining Basin. Through these visits, I noticed that each terril has a slightly different geology, vegetation, and transition stage, as well as a different relationship with its neighbors, and that a single terril is also made of several transition stages. I also discovered that in some of the visited sites, fruit seeds left behind by the miners have grown into trees. This means that observing the terril’s vegetation conditions is a way of indirectly reflecting on the imprints of the human presence that once existed on the site.

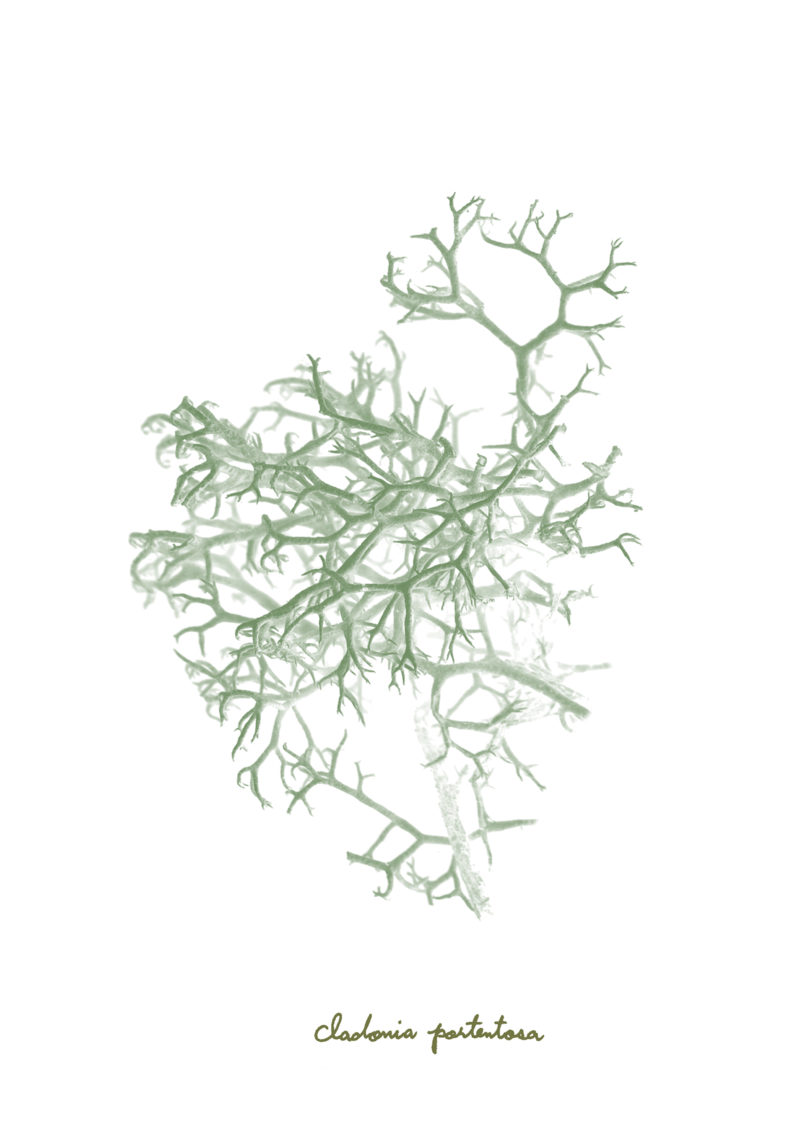

After these findings, I now believe that it’s not just the monochrome, but the subtly different colors of the soil and the complexity of vegetation associated with combustion, as well as the color differences (biodiversity) of each territory, that symbolize the “current terril”. This is why I wanted to suggest a new approach to the “black” terril, the symbol of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais mining industry, from the perspective of biodiversity, by using the colors of the plants, which symbolize the specificity and history of each terril, and the colors and patterns produced by the pH of the soil of each site and the different micro-organisms that inhabit them. The work thus consists of two different experiments:

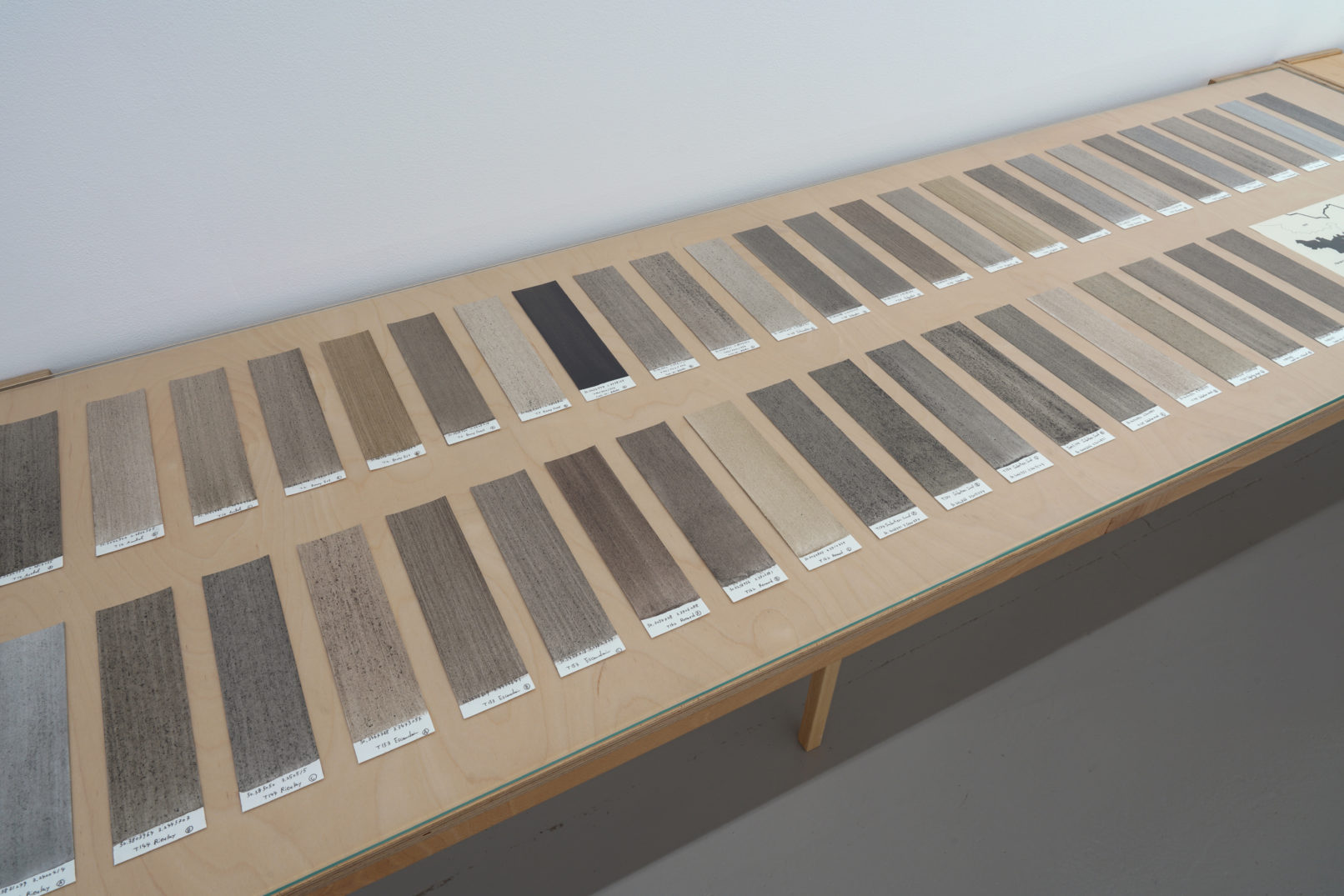

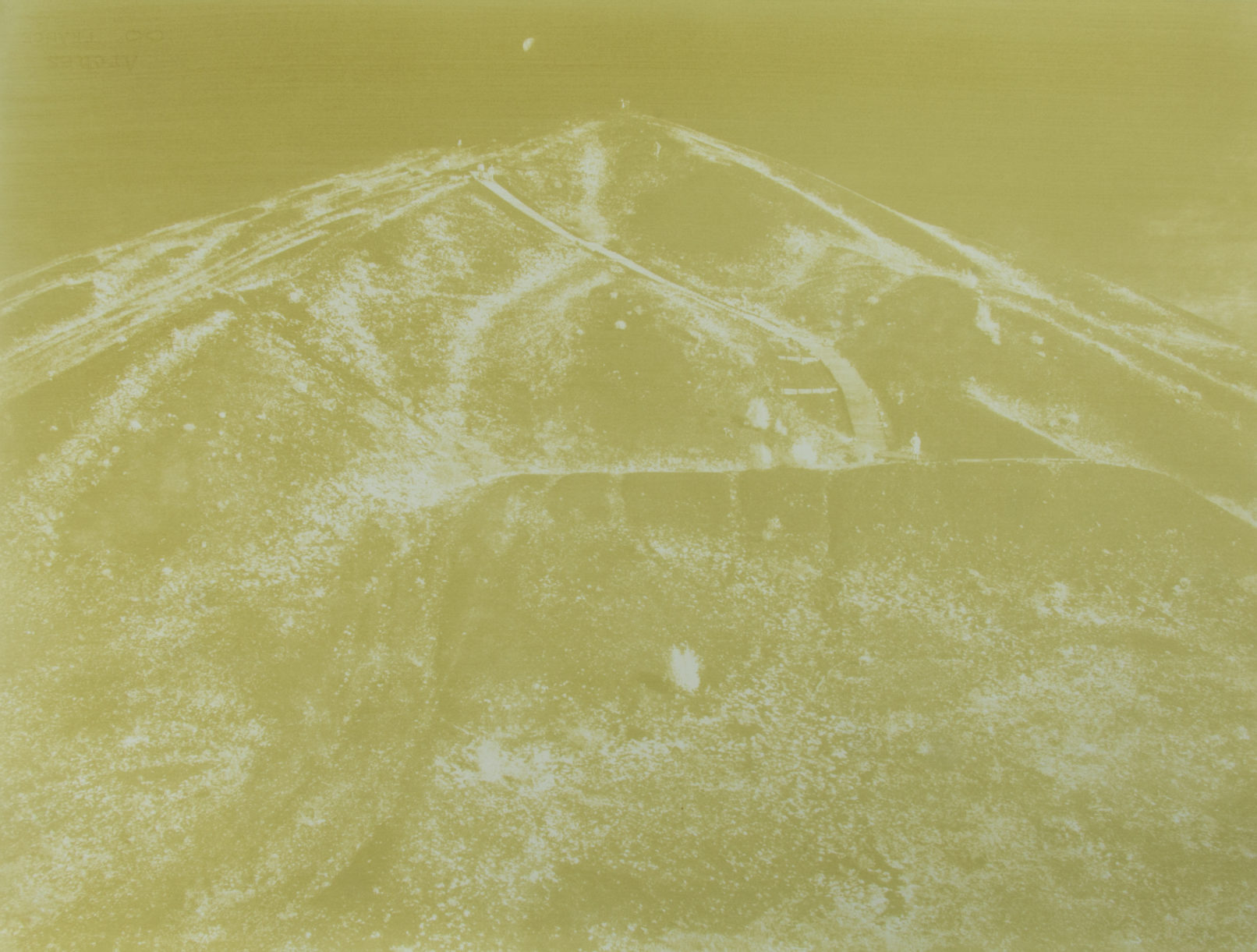

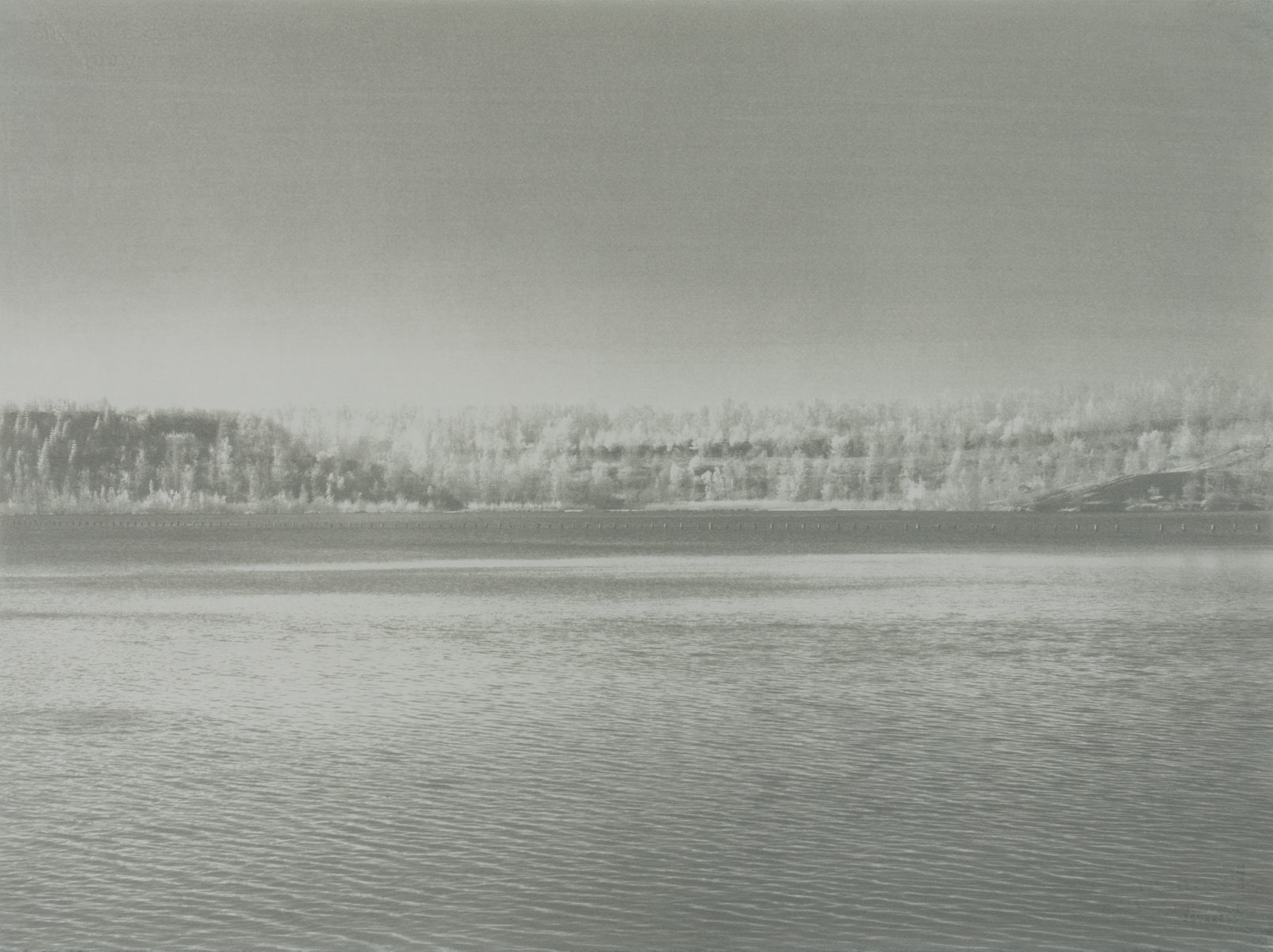

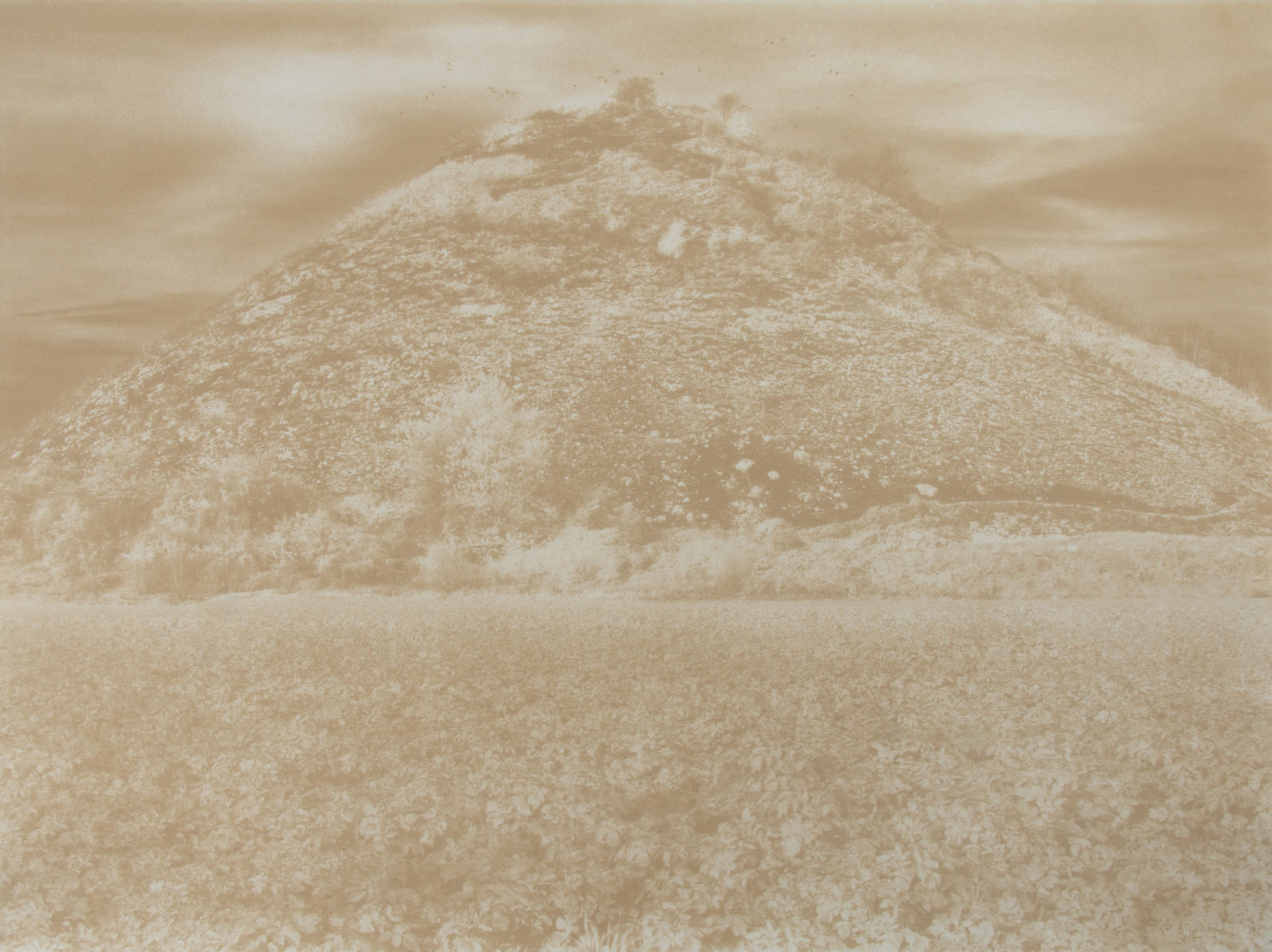

1. Photographic fossil of color and scent (link between photographic image, medium and scent)

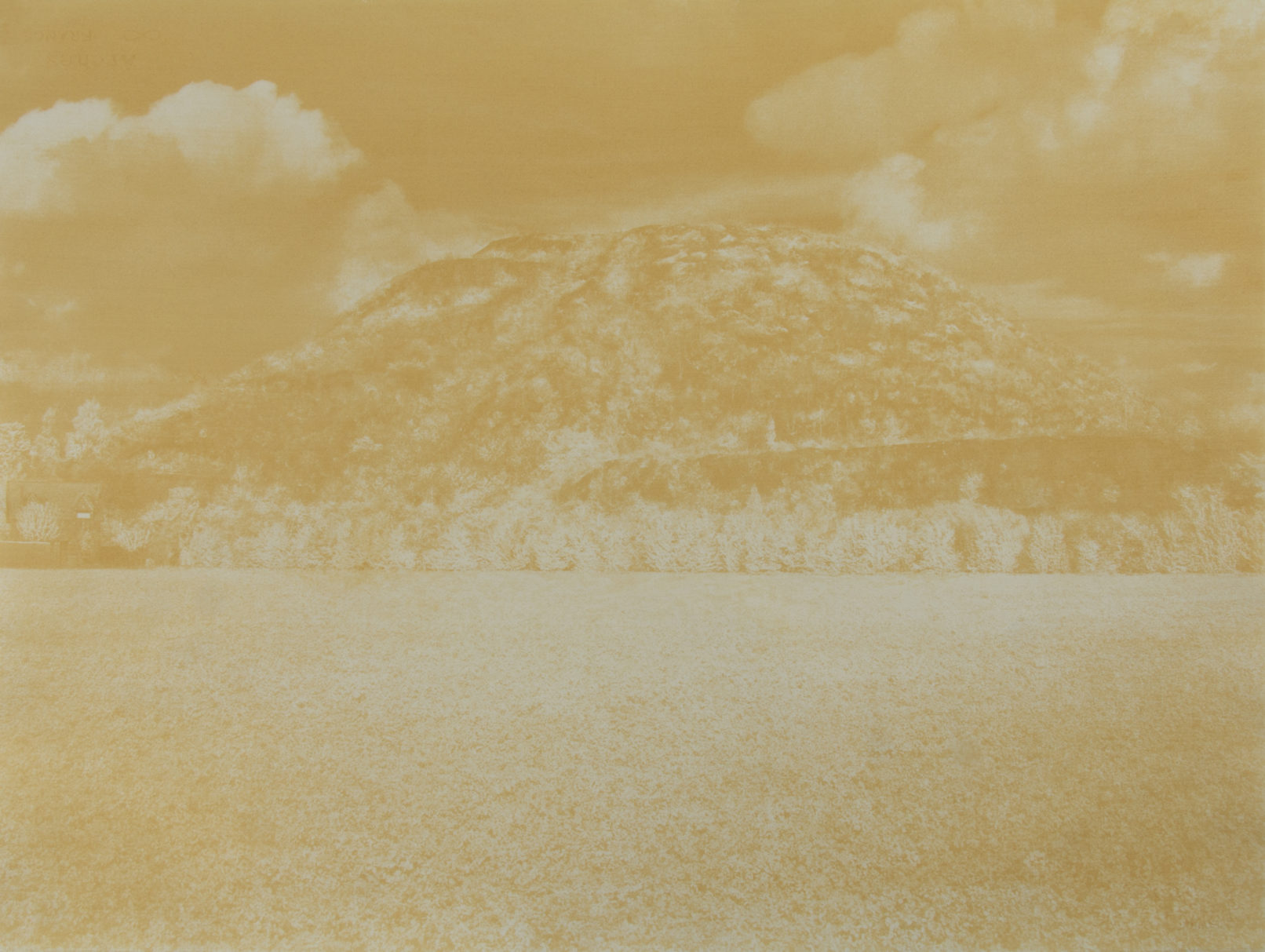

Take infrared photographs of the terrils to better visualize the differences in vegetation. Make pigments after collecting the plants that symbolize each site. These pigments are used to fix the infrared image using a photographic technique known as Gum bichromate, a non-silver photographic process invented in the mid-19th century. The plant pigments used are one of the components of the “color” of the photographed terrils. The scent of each pigment can also be one of the components of the scent of photographed terrils, evoking different memories for each viewer. A direct relationship between the medium and the fixed image, which is also part of the photographed terrils. Infrared photographs of 12 different terrils, printed in 12 different colors, symbolize approximately half the circadian rhythm of most organisms, that is, the movement of the sun.

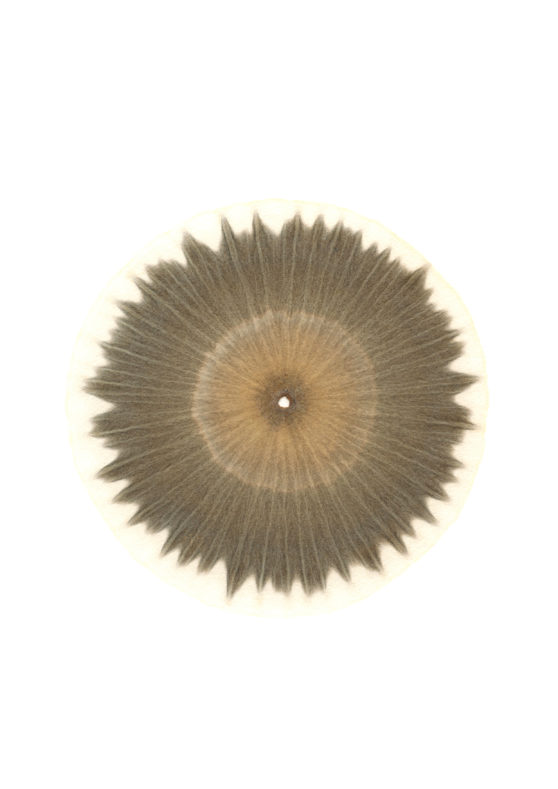

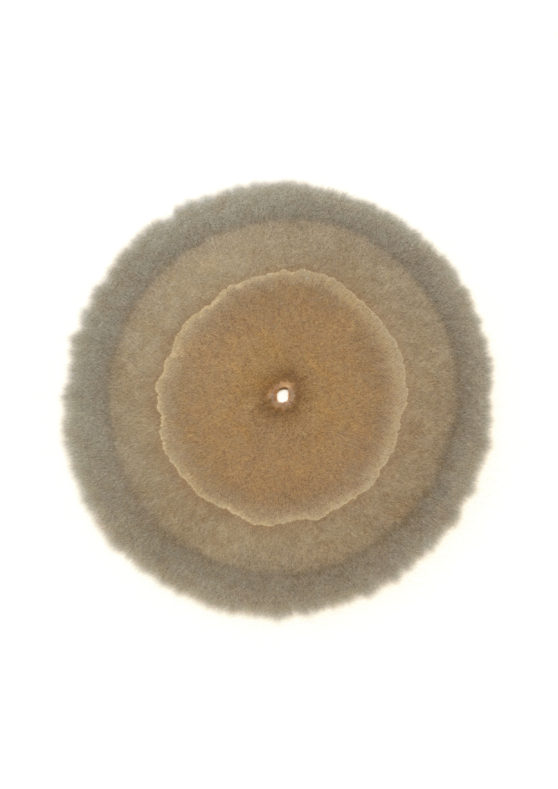

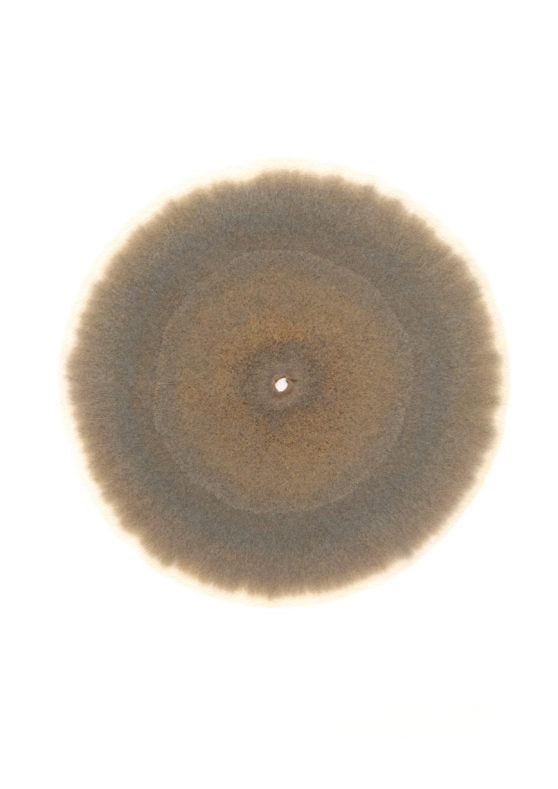

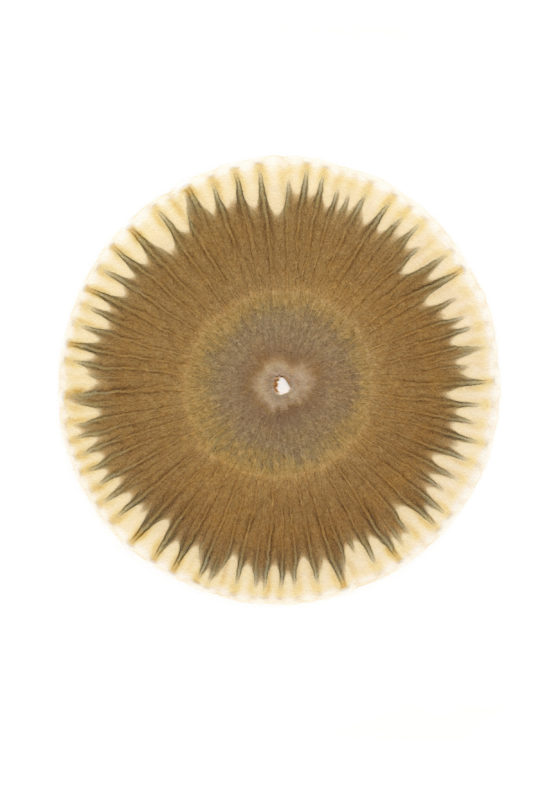

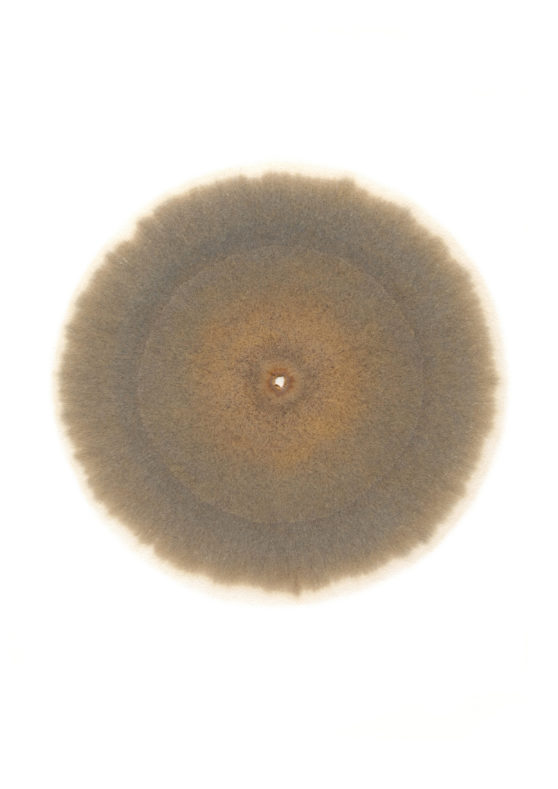

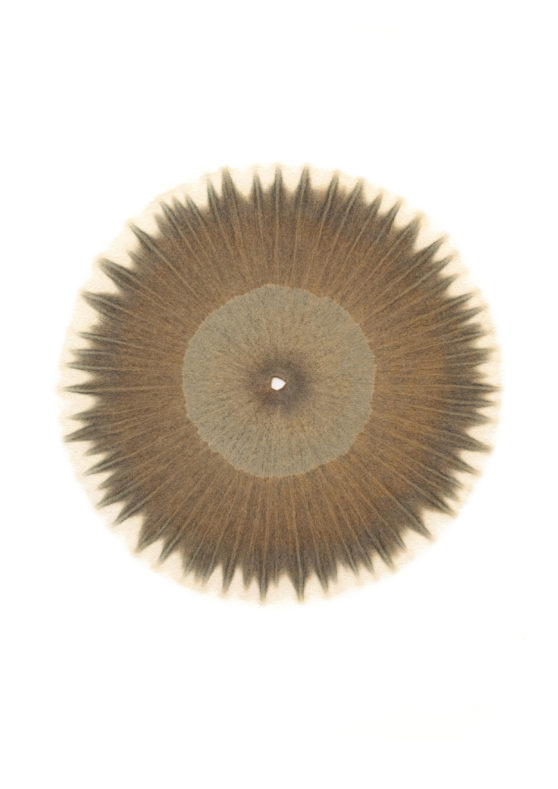

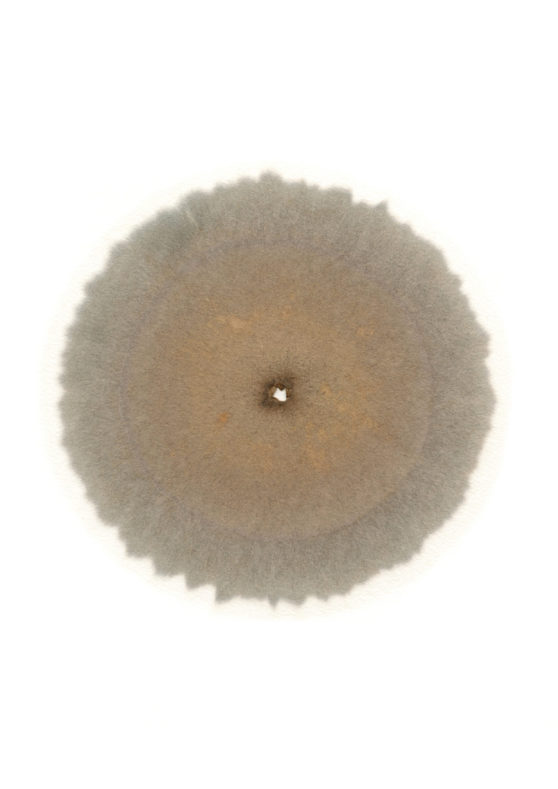

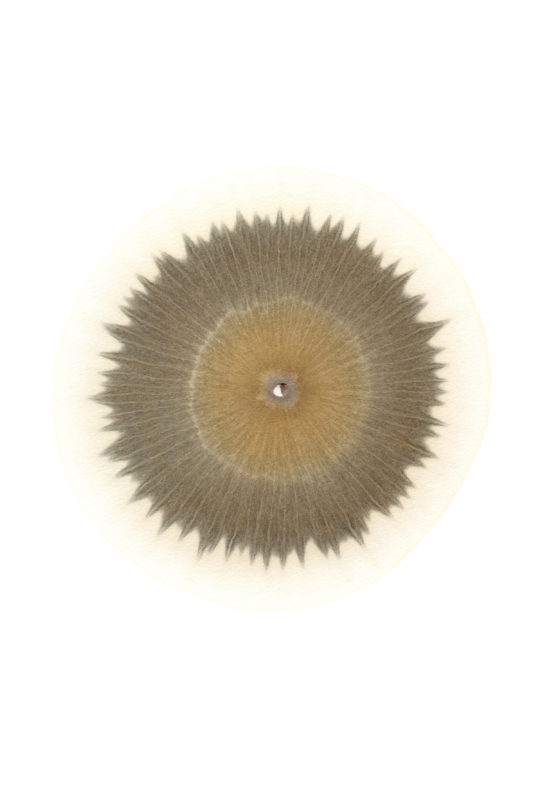

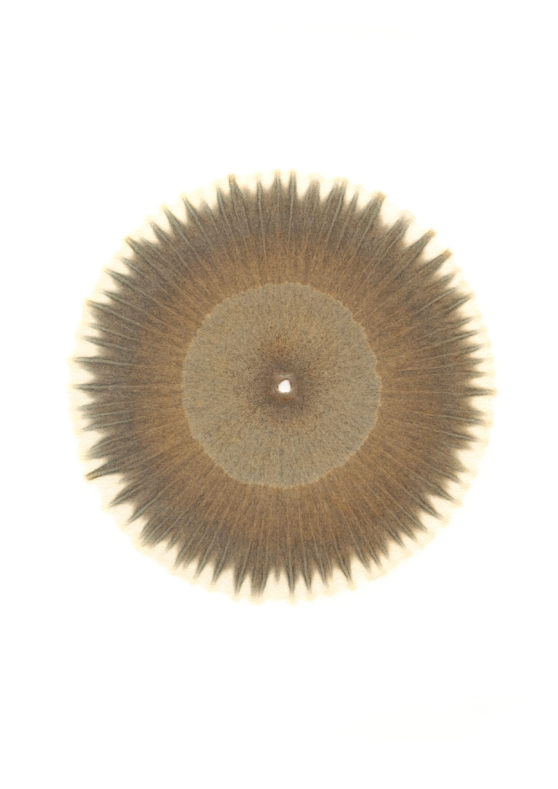

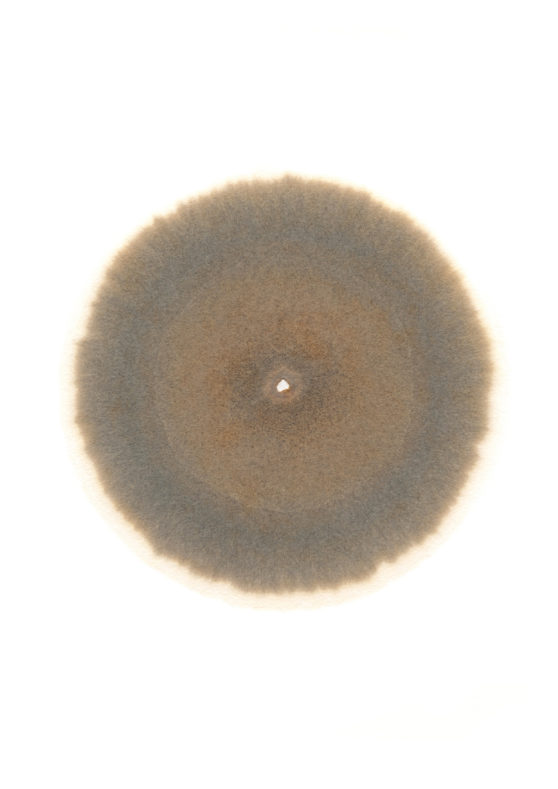

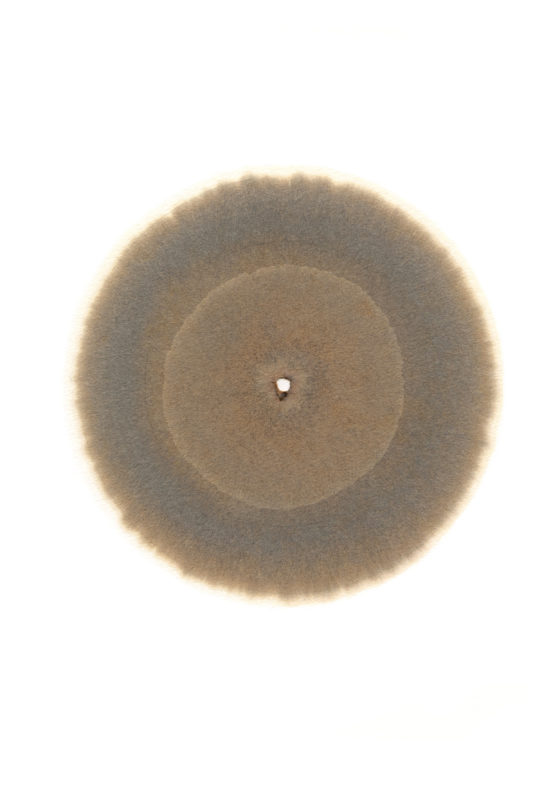

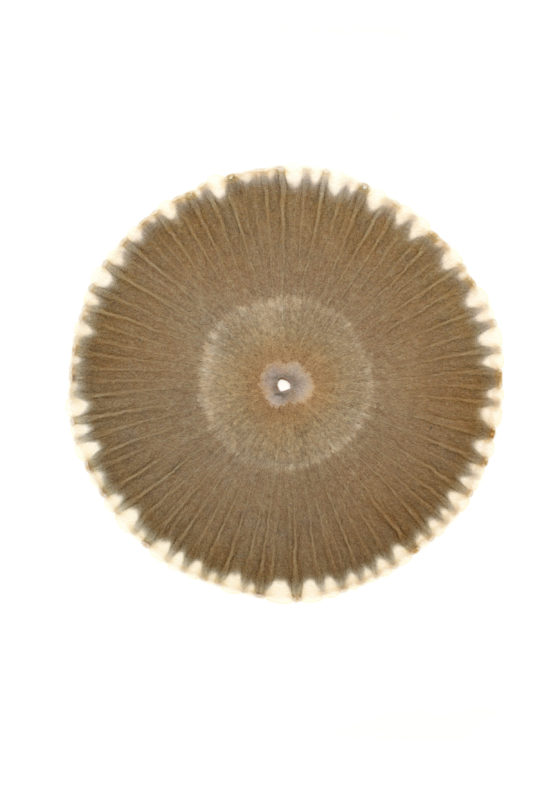

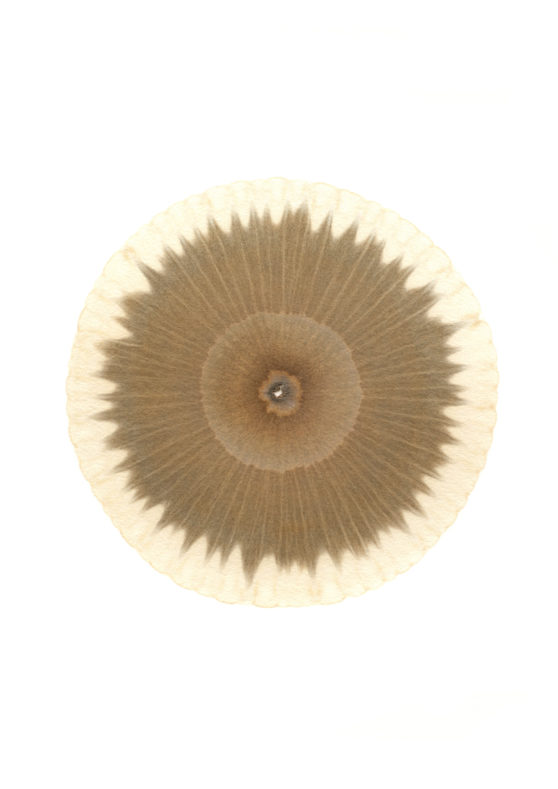

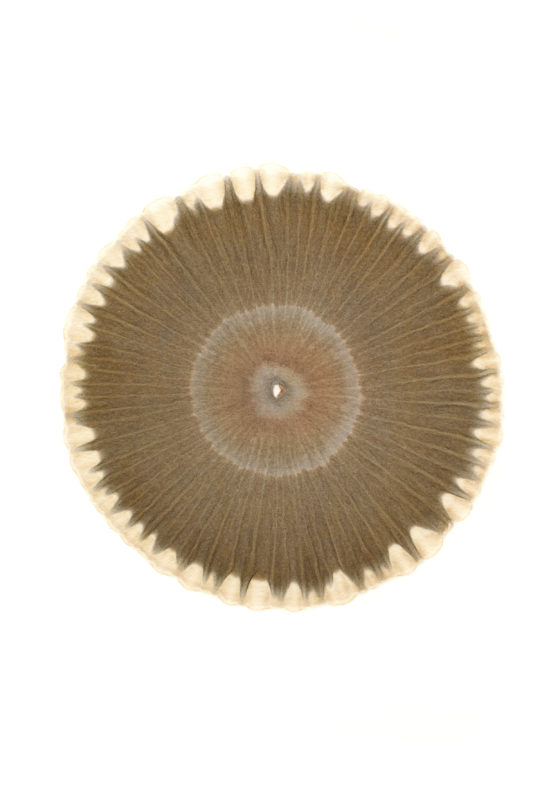

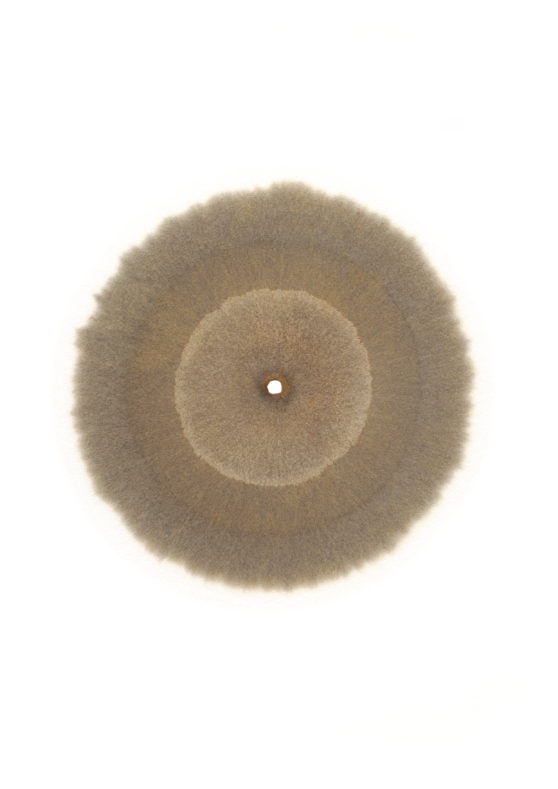

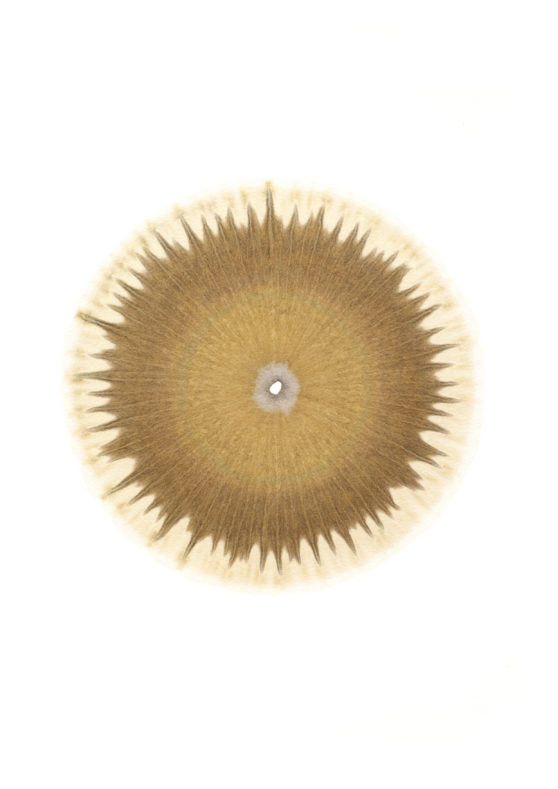

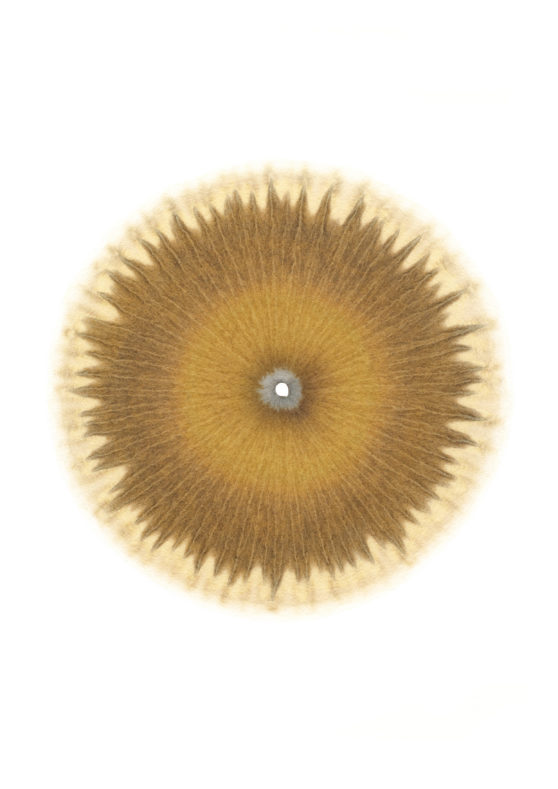

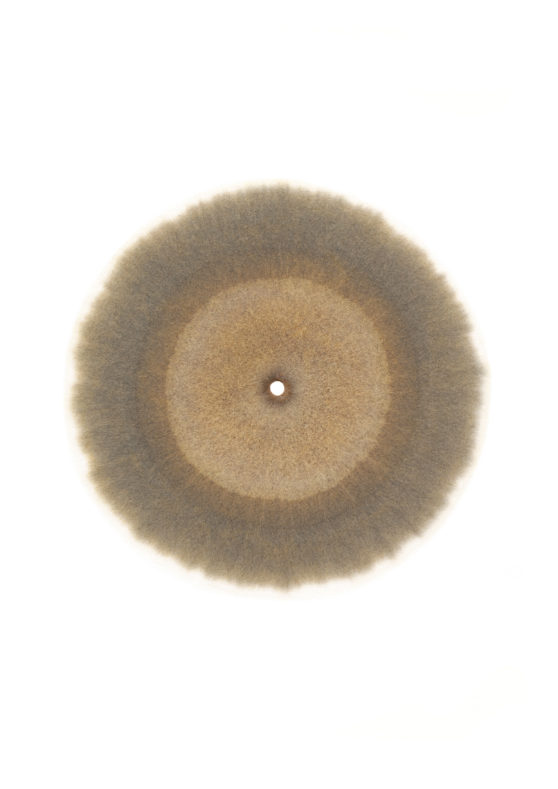

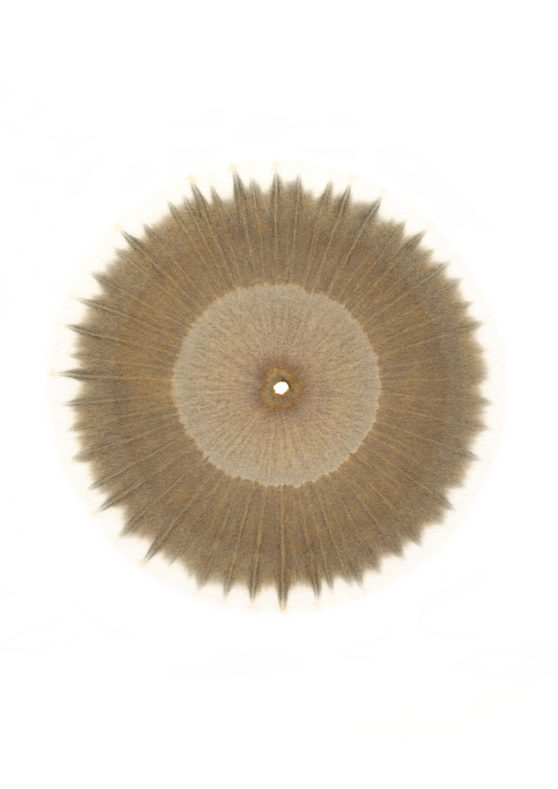

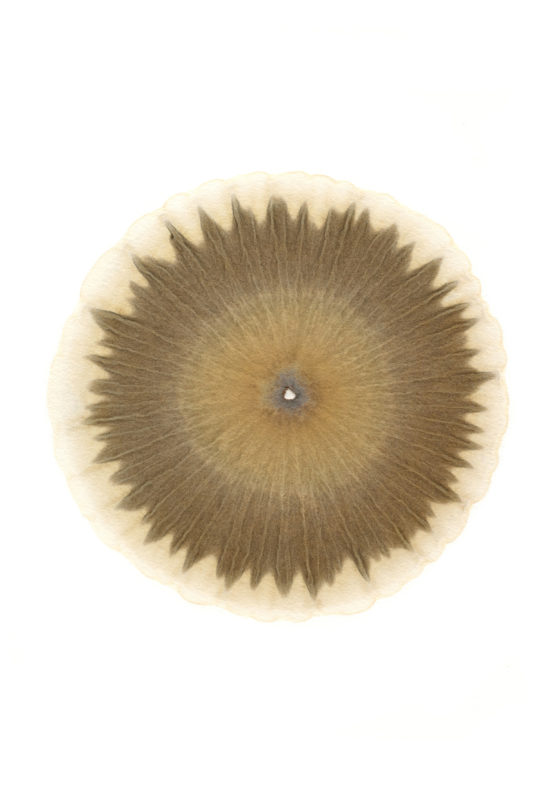

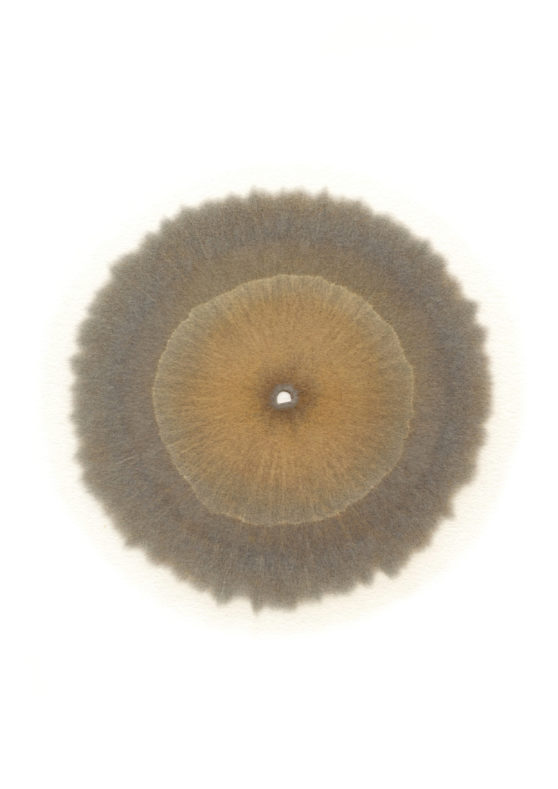

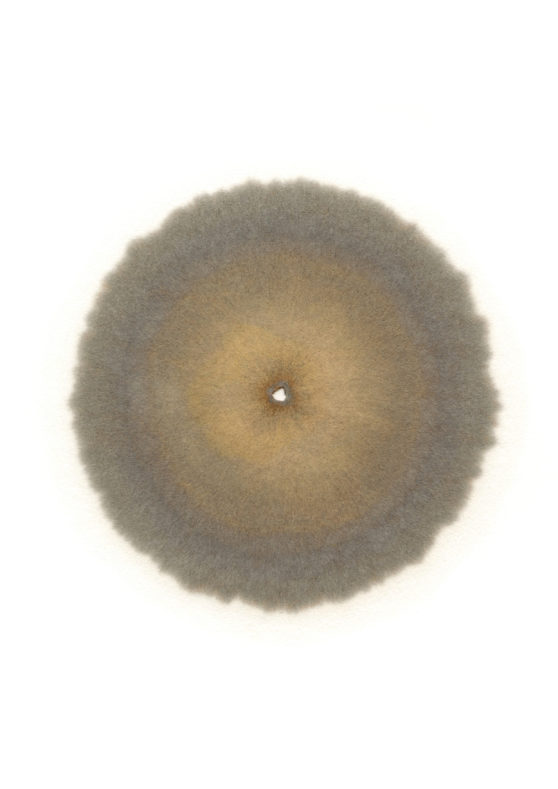

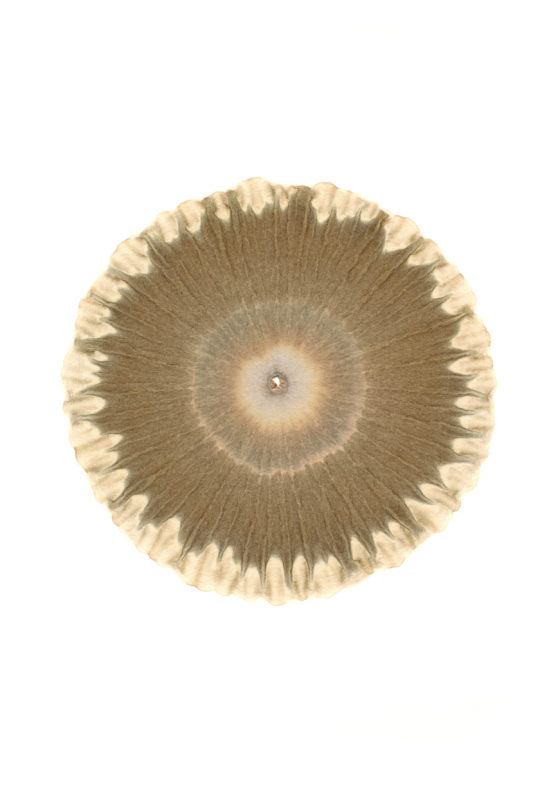

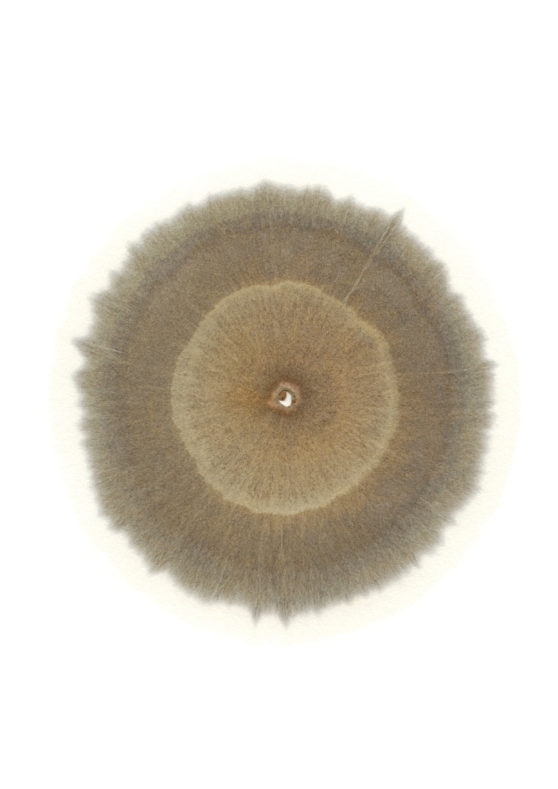

2. Soil mirror images (visible and invisible, the imaginary associated with them)

The presence of “soils”, closely linked to the state of vegetation at each site, is visualized using the soil chromatography, an analytical method of soil components proposed by German biologist Ehrenfried Pfeiffer in 1953. This analysis can be described as the fusion of a chemigram and a photogram in the sense that it involves a chemical reaction between a filter paper containing silver nitrate and a solution of dissolved soil constituents, using sunlight. Instead of limiting the analysis to the test method as described, propose a varied point of view, blending the randomness of the Rorschach test with the methods of scientific analysis, and freeing it from its role as an “analytical result”. The chemical reaction between silver nitrate and soil will continue gradually during the exhibition until the reaction stabilizes (about a month), giving rise to new details and colors. Just as the soil is alive, this is an attempt to give life to the images that have fixed their imprints.

Through this series of photographic experiments, I’d like to offer an opportunity to reflect not only on the past of mining regions, but also on the future in light of the past. That’s why, at a time when chemical pigments can be used to rapidly manufacture a large number of products of the same quality, I dare to use plant pigments, which are unstable and difficult to control, and to reproduce “forgotten colors” based on a dialogue between time and materials. Through this act, I’d like to restore the primordial relationship between man and nature, to resist being forgotten…

*Satoyama

Satoyama refers to the area between the city and primary nature, where a human-influenced ecosystem exists, including rice fields, forests, or ponds. It covers around 40% of Japan’s surface, and the relationship between Satoyama and the Japanese began around 3,000 years ago in Japan’s Yayoi period.

*Terril

A terril is a deposit of mineral wastes made up of schist, sandstone, and various waste materials from underground and surface mining operations (used rails, demolition waste, crossbar), and even other materials such as domestic waste, for example. At one time, the coal-mining companies were responsible for collecting the waste from the mining towns and then confining it to the edge or base of terrils.

Production supports :

CRP/ Centre Régional de la Photographie Hauts-de-France

DRAC Hauts-de-France

Mission Bassin minier

Cité des Électriciens

Centre Historique Minier de Lewarde

La Capsule – Résidence création photos

Special thanks :

Machiko Saito (coloriste)

Bernard Dhennin

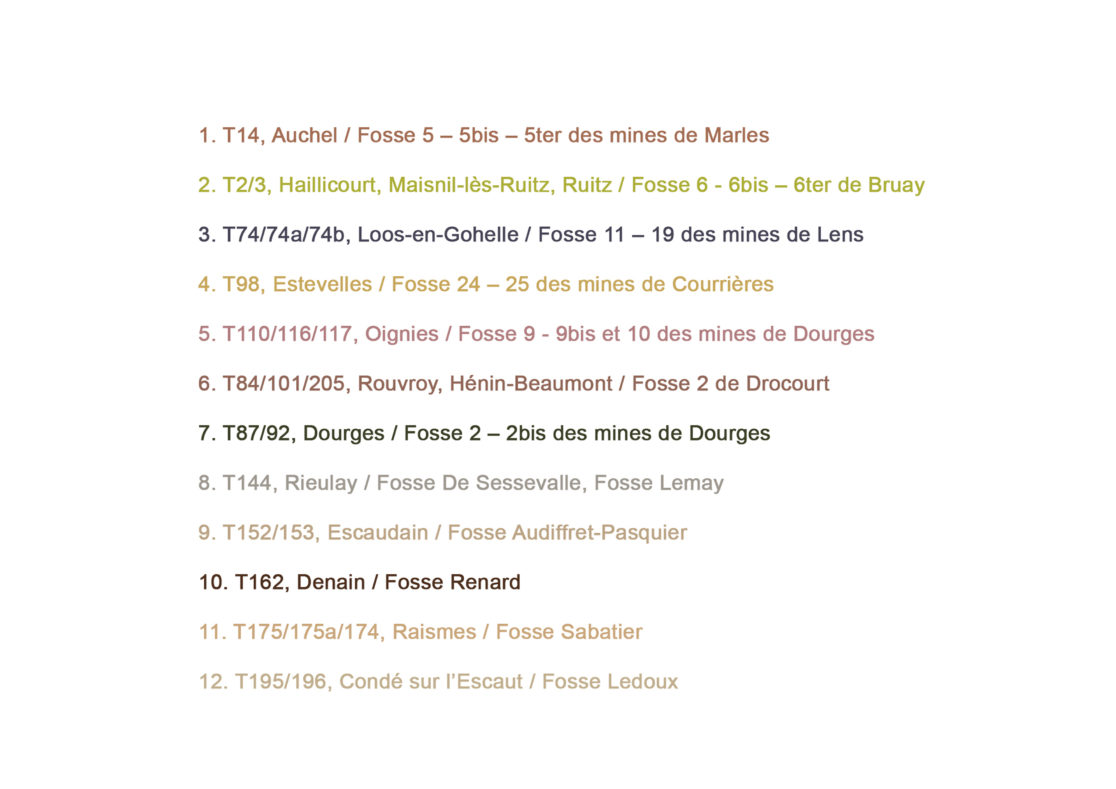

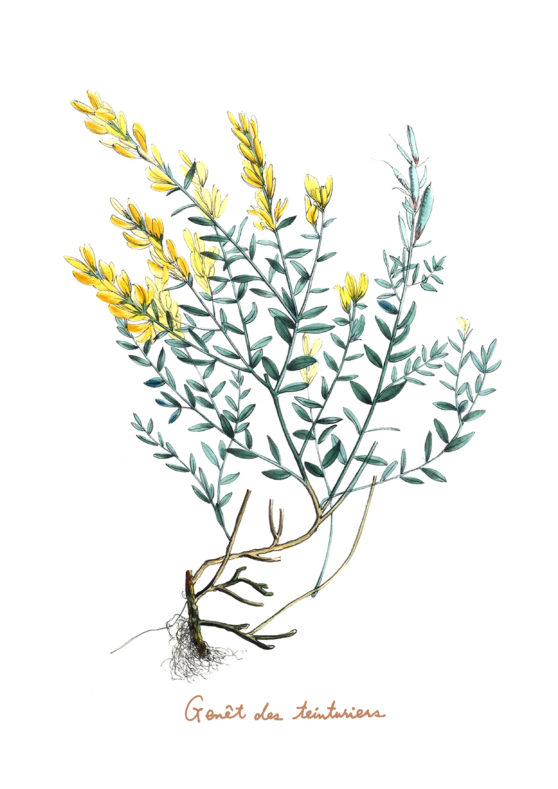

1. Terril 14 Auchel / Fosse 5 - 5bis - 5ter des mines de Marles / Genista tinctoria

2. Terril 2 and 3 Haillicourt, Maisnil-lès-Ruitz, Ruitz / Fosse 6 - 6bis - 6ter de Bruay / Reseda lutea

3. Terril 74, 74a and 74b Loos-en-Gohelle / Fosse 11 - 19 des mines de Lens / Anchusa officinalis

4. Terril 98 Estevelles / Fosse 24 - 25 des mines de Courrières / Arugula flowers

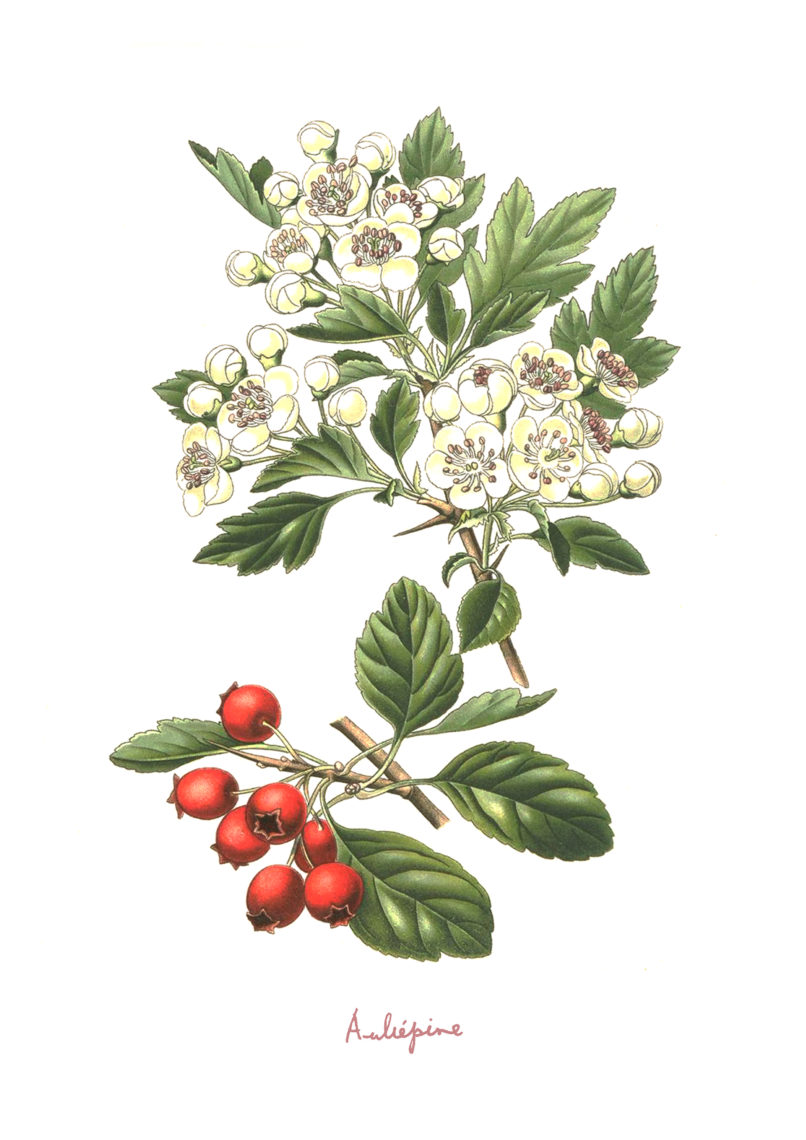

5. Terril 110, 116 and 117 Oignies / Fosse 9 - 9bis et 10 des mines de Dourges / Hawthorn and Meadow sage

6. Terril 84, 101 and 205 Rouvroy, Hénin-Beaumont / Fosse 2 de Drocourt / St Lucie cherry

7. Terril 87 and 92 Dourges / Fosse 2 - 2bis des mines de Dourges / Yellow horned poppy and Reindeer lichen

8. Terril 144 Rieulay / Fosse de Sessevalle and Fosse Lemay / Blackthorn

9. Terril 152 and 153 Escaudain / Fosse Audiffret-Pasquier / Verbascum

10. Terril 162 Denain / Fosse Renard / Common bracken

11. Terril 175, 175a and 174 Raismes / Fosse Sabatier / Silver birch

12. Terril 195 and 196 Condé sur l'Escaut / Fosse Ledoux / Great yellowcress