Rétine (miroir d’hortillonnage – artistic commission for International Garden Festival – Hortillonnages Amiens)

2025〜 (on going research and production)

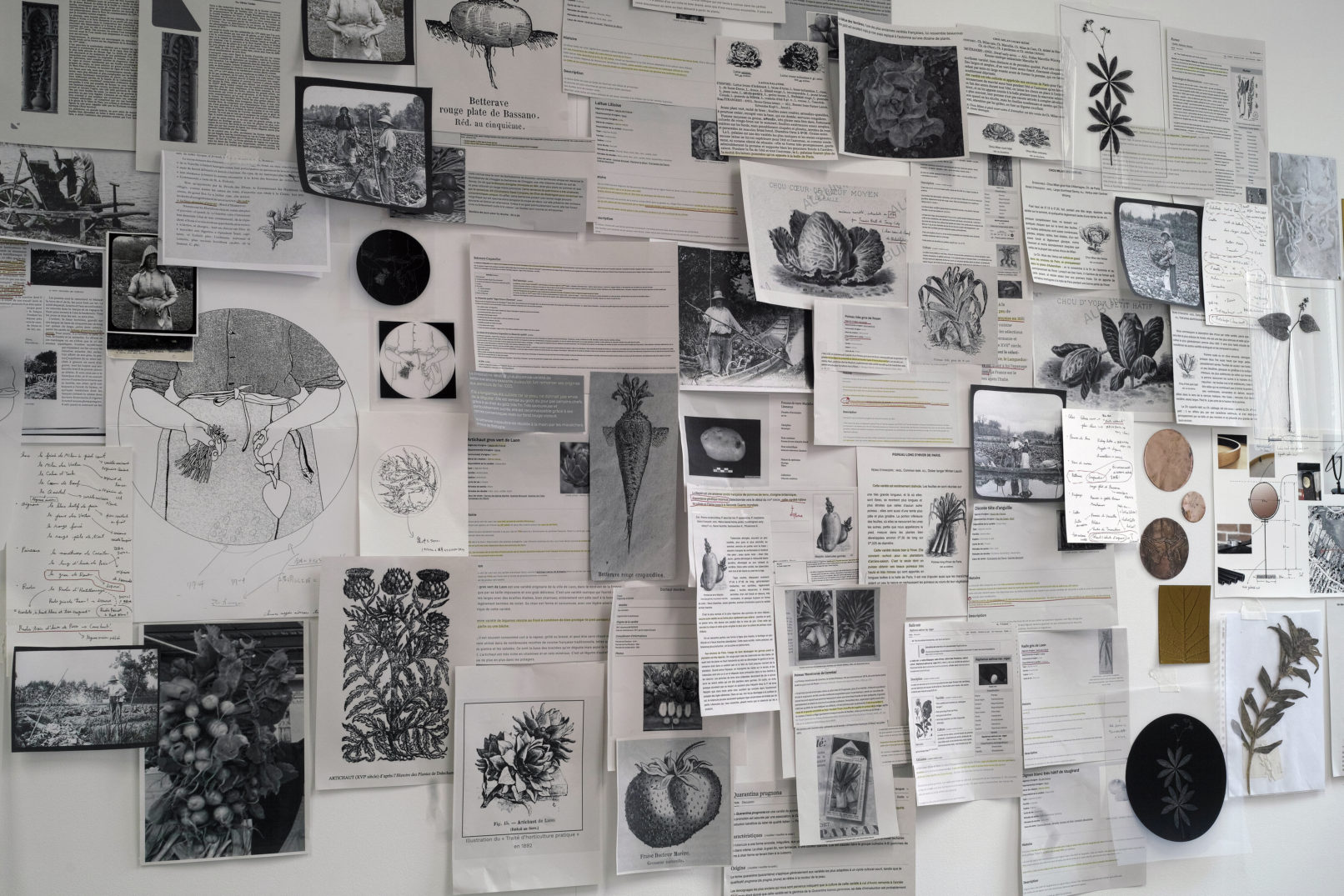

The history of photography is also the history of the development of technologies that enable us to capture fleeting images drawn on our retinas on various media, and of the evolution of our perception of reality. Accidental marks and misconceptions gave rise to various photographic ideas and prototypes that shaped the history of photography as we know it today. It is these traces of several photographic births that exist around the history of photography that interest me most today. By focusing on these forgotten drafts, I discover fundamental elements of this medium. The relationship between natural phenomena and photography, as well as “the desire to see.” As I continued my research into these photographic ideas, I discovered the “Makyo (magic mirror)”, a bronze mirror that is believed to have existed since the 1st century BC, during the pre-Han dynasty. It was this ancient technique that inspired this work entitled “Retina.”

In Japanese tradition, the sun was considered the supreme deity that governed life through its close connection to agriculture. This is why the veneration of the sun was strongly reflected in many rituals and beliefs, which have been passed down to the present day. Reflecting this, as shown in the “Yata-no-Kagami,” one of the three sacred objects of Shintoism, mirrors have been considered the symbol of the sun goddess (Amaterasu) in Japan since ancient times, due to their ability to reflect light, and are used in rituals and as funeral accessories.

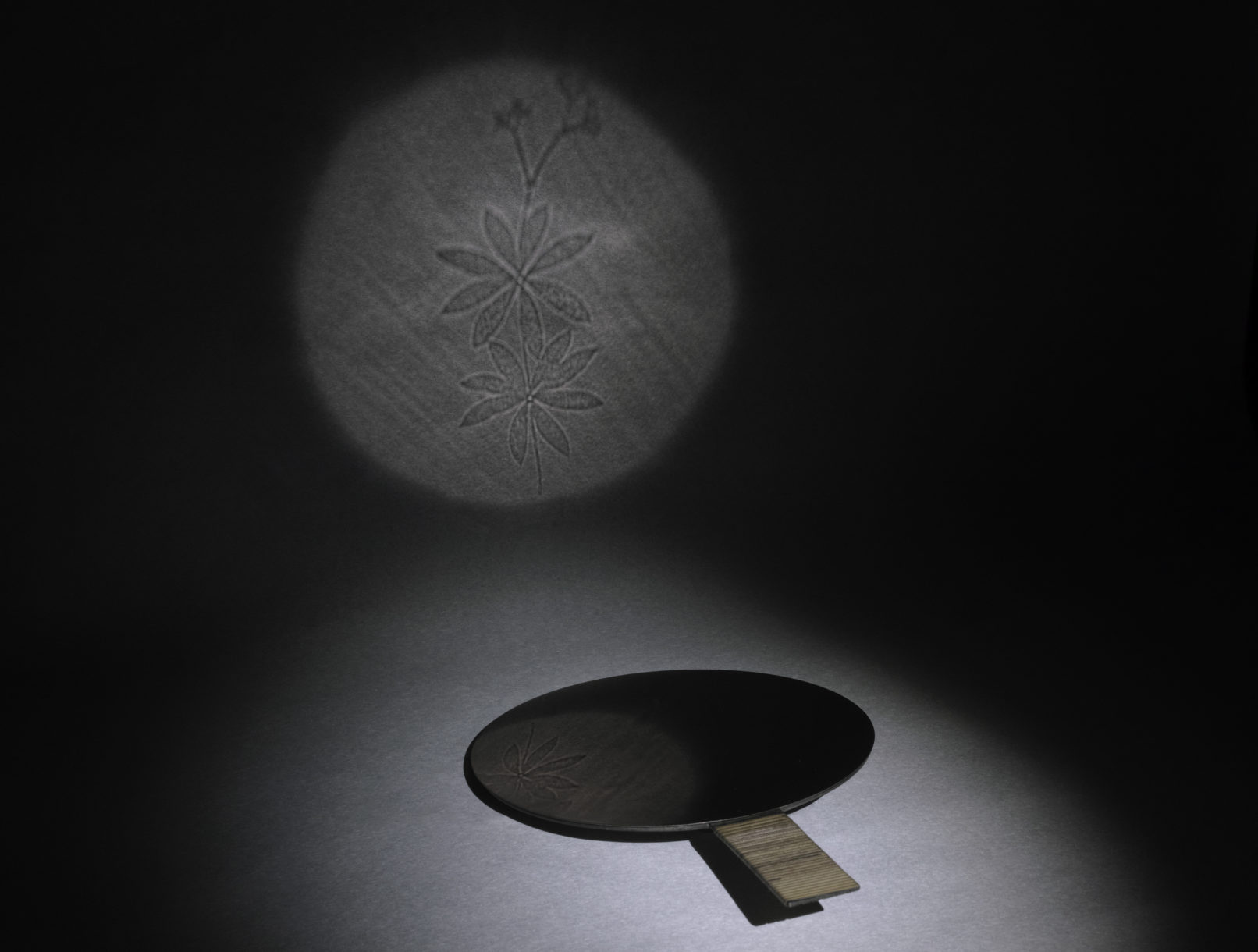

The reason why Makyo occupies a unique place among them is due to a particular optical phenomenon: by leaving tiny irregularities (image) on the surface of the mirror, it is possible to project this hidden image. Just as in Europe, people found something magical in the image projected by the magic lantern, Makyo also caused fear among the Japanese. Furthermore, recent scientific research and reproductions using 3D printers have revealed that a type of copper mirror called “Sankakubuchi-Shinjyu-Kyo (sacred animal mirror with a triangular edge),” used by Himiko, the queen of 3rd-century Japanese mythology from Yamataikoku, was a Makyo. This means that by using this mirror, Himiko projected the symbols of gods and spirits engraved on it to be seen by the people as a shaman who controlled the sun. The magic mirror technique was also used to hide the image of Christ (symbol of faith) during the persecution of Christians in the early 16th century, and hidden believers would pray to the image projected by sunlight. Because of this historical context, the images and words projected by this mirror were considered both “words of God” and “sorcery” due to their association with shamanism. In my opinion, this story resonates with the “words of light,” as described by William Henry Fox Talbot in his research notebook for his invented technique, and the surface of the daguerreotype, which was called a “mirror that remembers.”

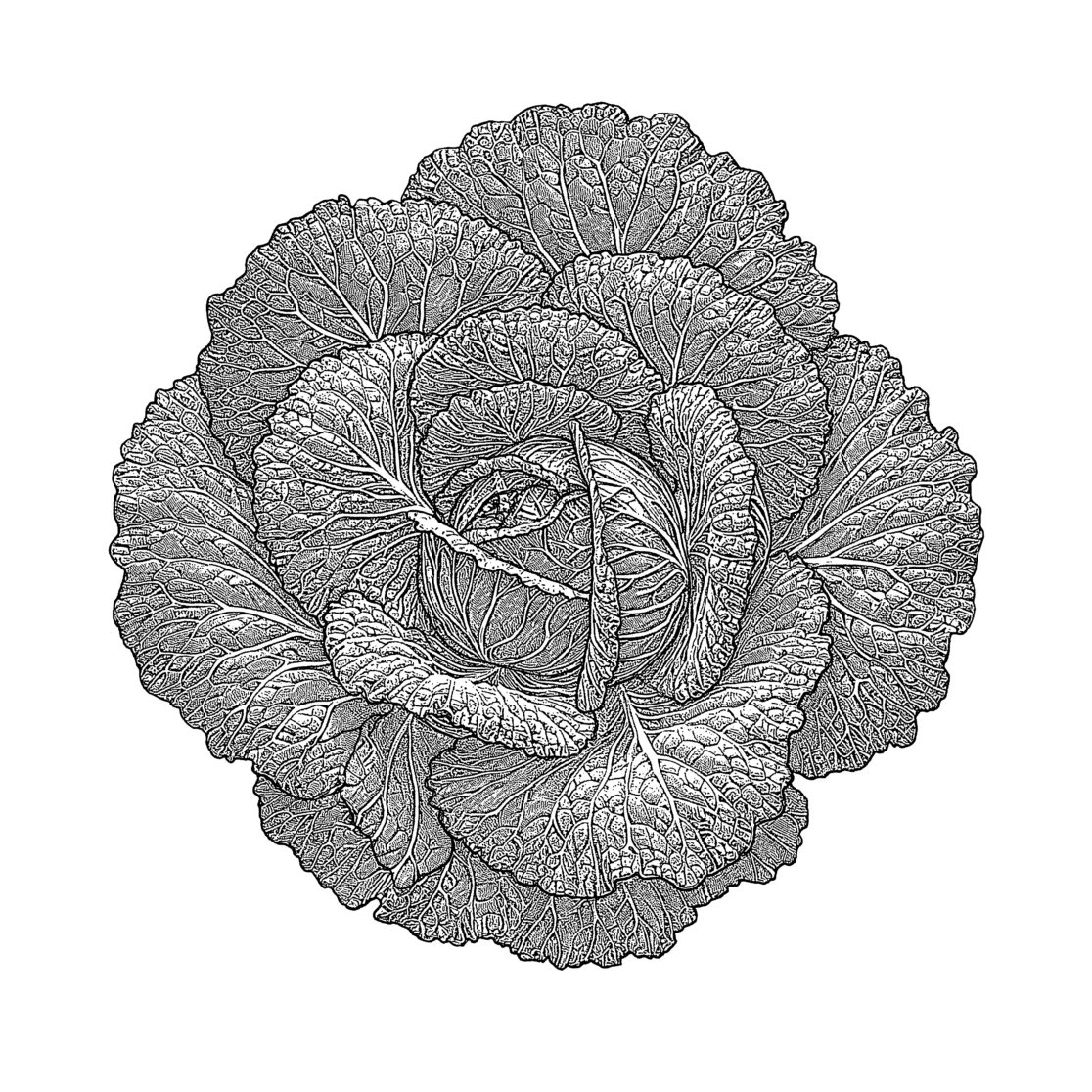

Based on this process of reflection, “Retina” attempts to experiment with the subtle relationship between what can be seen by sight and what cannot be seen, combining heliography (an ancient photographic technique) and the Makyo technique. In particular, drawing on the fact that W.H.F. Talbot’s early photographic experiments began with his efforts to permanently preserve the shadows of plants in his garden (photograms), as he states in his 1844 book “The Pencil of Nature,” I attempt to superimpose the projected images of these plants as constantly changing environmental indicators and ephemeral images projected onto the retina by hiding photograms of vegetables grown in the hortillonnage of Amiens, particularly those that can be grown again due to climate change, in the reflection of a mirror. These shadows, projected onto the viewer by the reflection of sunlight, are reminiscent of the projected image of the Camera Lucida, the optical device that gave rise to the idea of photography. By exploring primitive optical phenomena—reflection and projection—Rétine raises a new question about the meaning of the act of seeing. I seek to understand how light and image, both ephemeral and permanent, can bear witness to a constantly evolving reality. This optical installation becomes a reflection on the role of photography, which, through light and shadows, captures fragments of reality while confronting us with the invisible.

Production supports :

l’Institut pour la photographie des Hauts-de-France

Verbrugge Performance Coatings

Vincent Valenduc (V-Forge)

Installation Photos :

Yann Monel