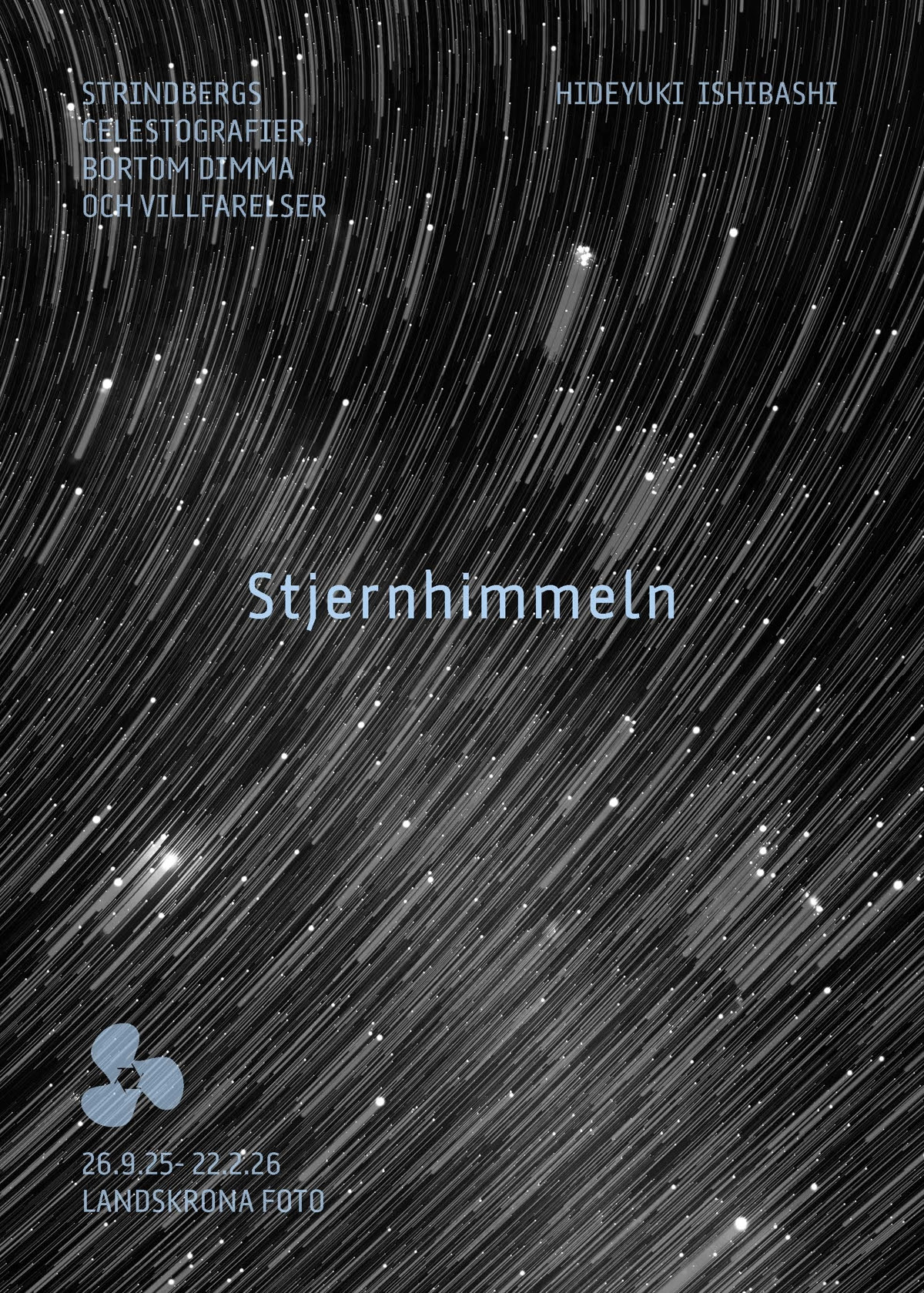

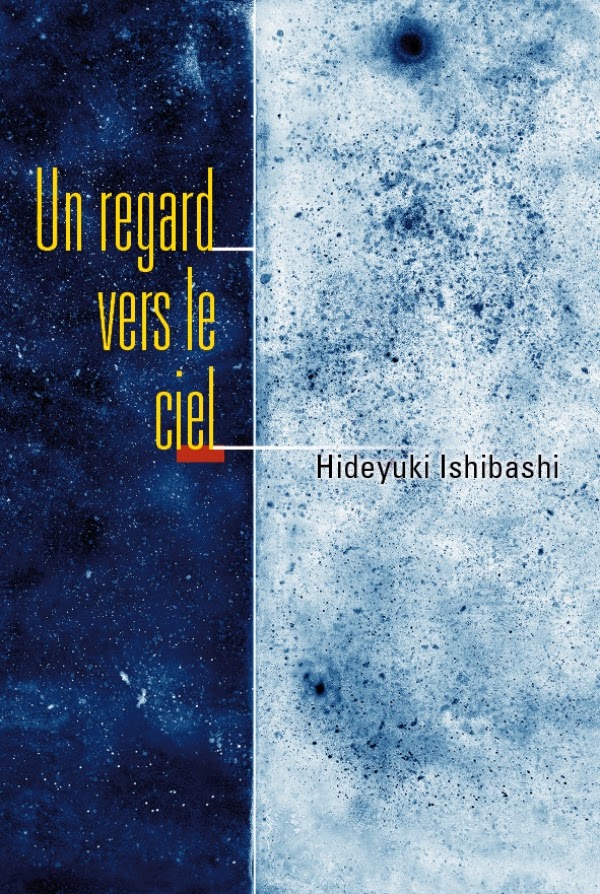

Stjernhimmeln (the heavenly sky)

2018 - 2025

During the 1850s and 1860s, photography was seen primarily by painters as a new pictorial technique, a trend that gave rise to many professional photographers. Writers such as Émile Zola and Lewis Carroll were also attracted by the potential of the photographic medium. Perhaps one of the most unusual of these early amateur photographers was the Swedish playwright, philosopher, painter, composer and alchemist August Strindberg. From an early age in his creative process, he was interested in the relationship between representation and the objectivity of the photographic medium and approached photography as a “tool for experimentation”. In particular, most of his photographic experiments in the 1890s served to exploit his vast knowledge of optics and chemistry to focus on color photography or light analysis. For this reason, many of his photographs have no specific subject but “traces of natural phenomena”. However, many of them are “hypothetical scientific photographs” influenced by alchemy and the ancient sciences (natural philosophy), in other words, the results of “pseudo-science” without analytical justification. Among the his photographic experiments produced during this period, the most enigmatic, raising fundamental questions that are still relevant today, such as “what is truth or faux in science?’’ and “what is photography?”, is that of the “Celestographs”, the subject of this art project “Stjernhimmeln (the heavenly sky)”.

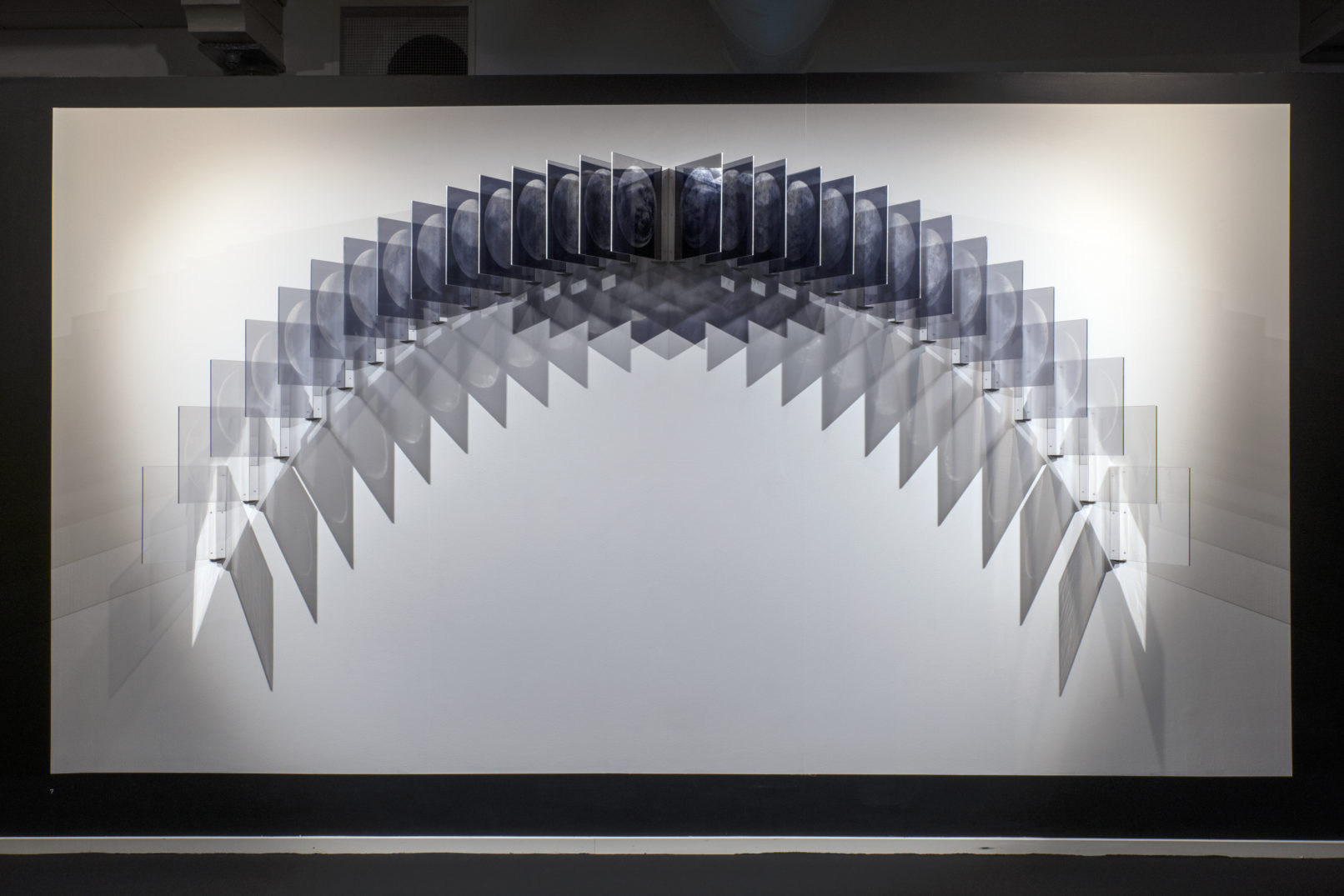

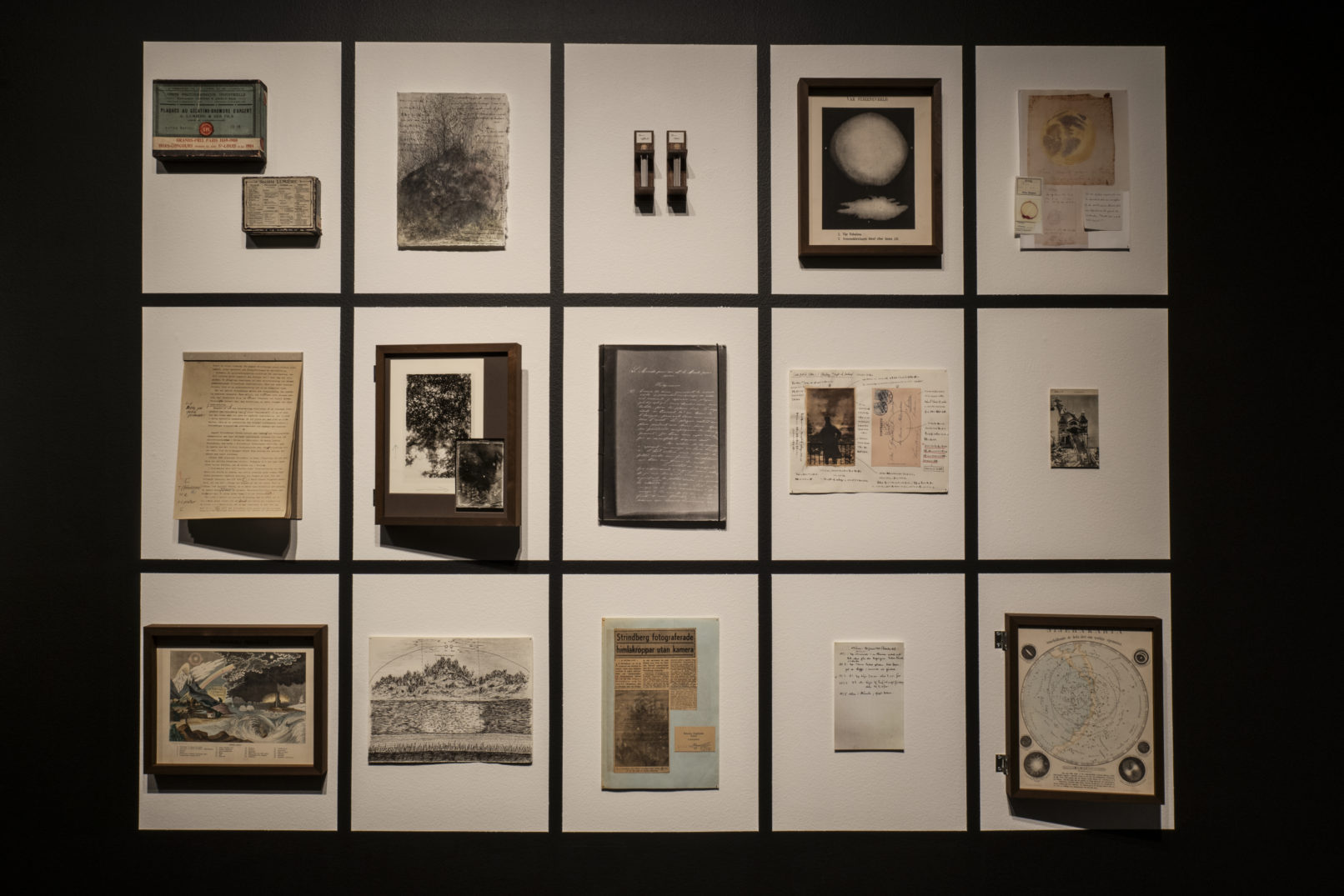

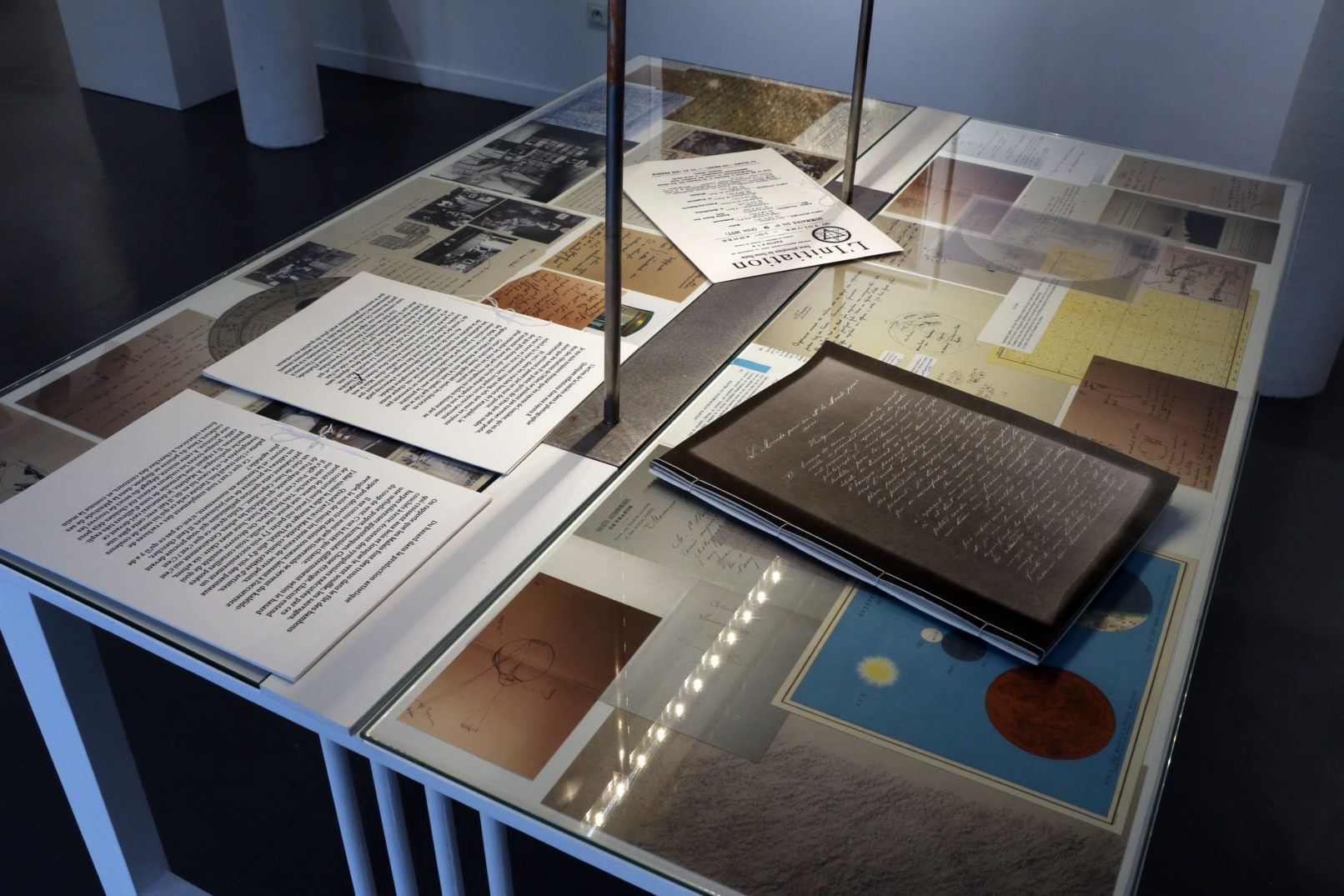

The Celestographs by Swedish playwright August Strindberg, the result of a philosophical influence from Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche and a fusion of natural science and occultism, were produced at Dornach Castle, Upper Austria in December 1893 – probably March 1894 at the dawn of the 20th century, a period of industrialization and modernization. One of the essential features of Celestographs is the absence of a camera and optics. To demonstrate that our perception of the world is an illusion limited by our eye and its construction, Strindberg exposed photographic plates directly to the moon, sun and stars, capturing their shape without distortion from our eyes. The result was an irregular pattern of tiny dots, like a trace of light, which he believed had captured the true appearance of the constellated sky. As a way to develop the image as efficiently as possible, he also exposed the photographic plate by leaving it in the developing solution, which resulted in more chemical effects, revealing a pronounced “heavenly sky” effect. Therefore, he sent several Celestographs along with a 13-page letter “Le monde pour soi et le monde pour nous (the world for itself and the world for us)” to French astronomer Camille Flammarion to prove that using a telescope limits the light of the celestial body and distorts its true appearance. We don’t know why Flammarion became interested in Celestographs, but his book “Les caprices de la foudre (the unpredictability of lightning)”, published in 1905, suggests that he was interested in “traces of nature established by coincidence”: “Lightning photographs (…) the images it produces are reproductions, the skin of those touched serves as a photographic plate in the natural process of image production”. It’s also possible that he believed unknown natural phenomena had been captured accidentally on Celestographs, as evidenced by the fact that when Flammarion and Strindberg later met in Paris, he asked him to reproduce the experiment at the Société Astronomique de France (X-rays were discovered in 1895). His research was presented at a monthly meeting of the Société Astronomique de France on May 2, 1894, but no one took his research seriously once they realized that these photos had been taken without a camera or lens. Strindberg’s refusal to reproduce his experiments at a monthly meeting meant that his research was never pursued, but he never changed his ideas until the end of his life.

In fact, we know that the information captured on these plates is not starlight. On the other hand, these images of “the heavenly sky” remind us of the invisible link between light-sensitive material and the subject, because the relationship with the night sky is not direct but implicit. Just as naturalist philosophers and mystics have sometimes used photography to decode observed phenomena, seeking to capture their hidden nature, so the alchemist in Strindberg also appreciated the poetry and supernaturalism of the image appearing during chemical reactions, the “inner nature” of the photographic medium, a chaotic beginning where everything is still boundless and vague, “everything exists in everything !”. That’s why some Celestographs are unfixed, to return the photographed image even to nature, as Strindberg says; “something made by nature as well as a piece of nature”. The positive images of 16 Celestographs are preserved in the Royal Library of Sweden, but all the original glass plates have disappeared. Moreover, due to their extreme fragility, the originals are never exhibited, but kept in a separate room to prevent deterioration, and are rarely seen. In other words, the photographic image that existed to be seen is not seen to preserve its appearance, like the first photographic image that no longer exists by Thomas Wedgwood and Humphry Davy. In thinking about lost images, we begin to face a paradox of being seen and seeing that is caused by technical errors, misconceptions and disappearance (Schrödinger’s cat).

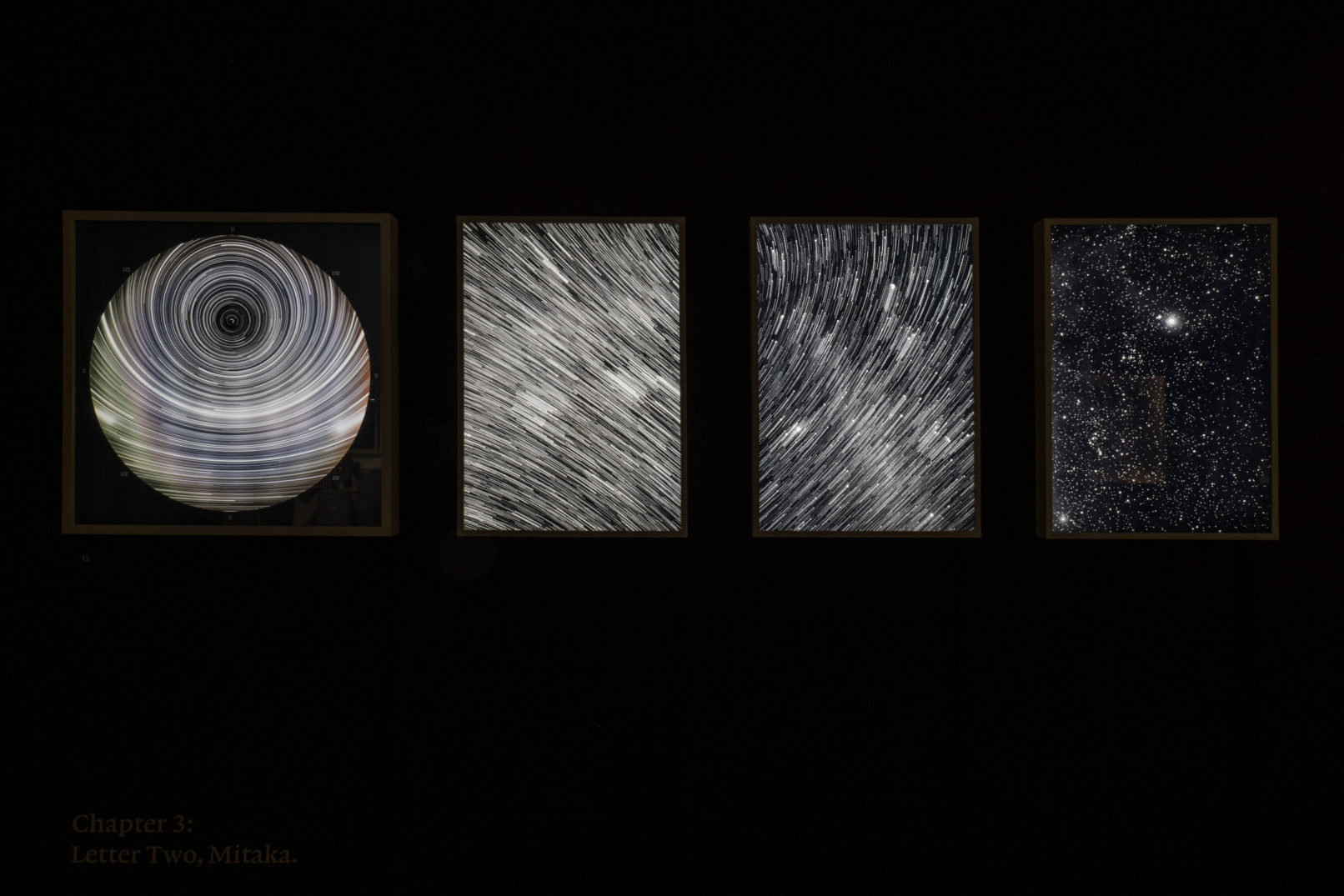

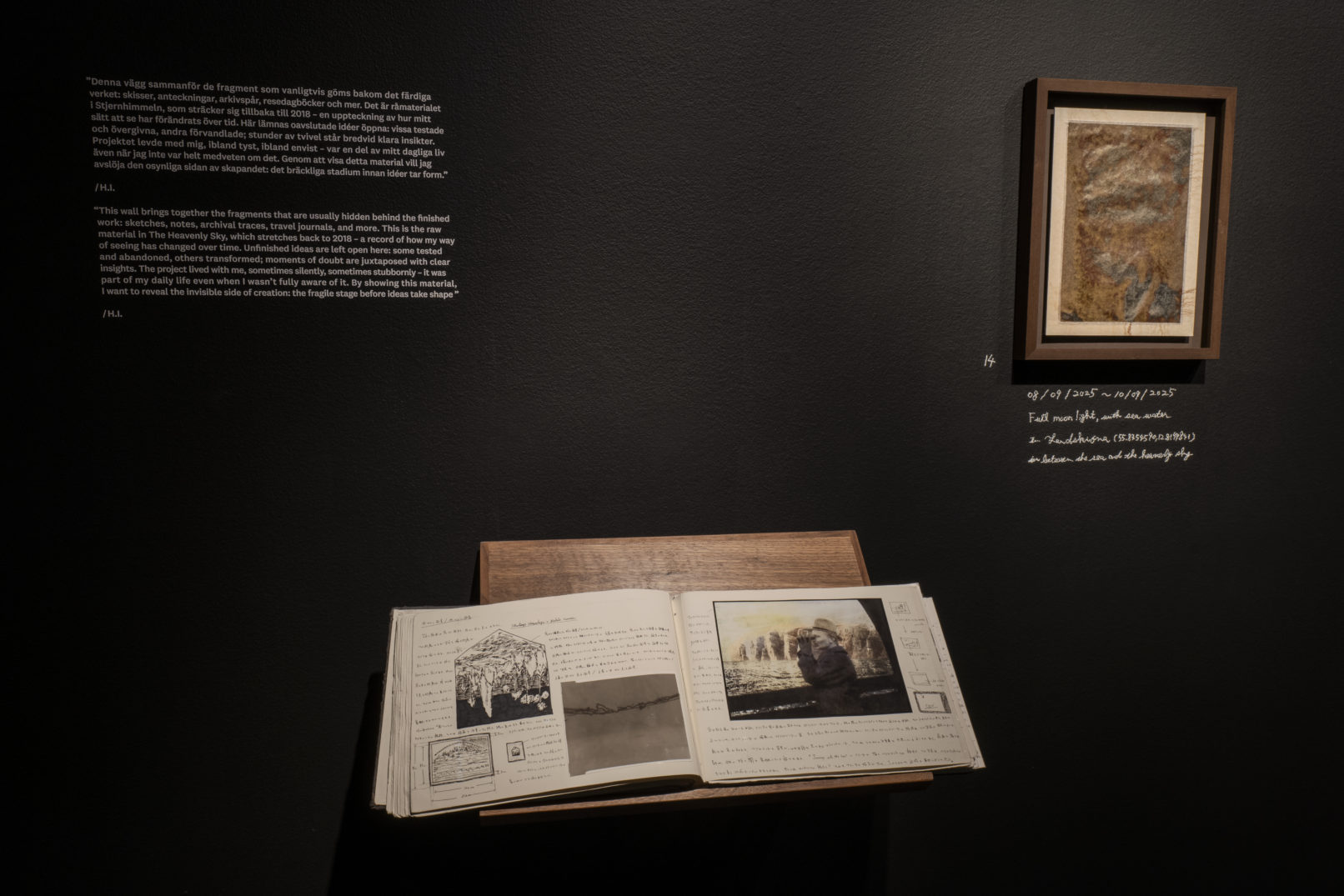

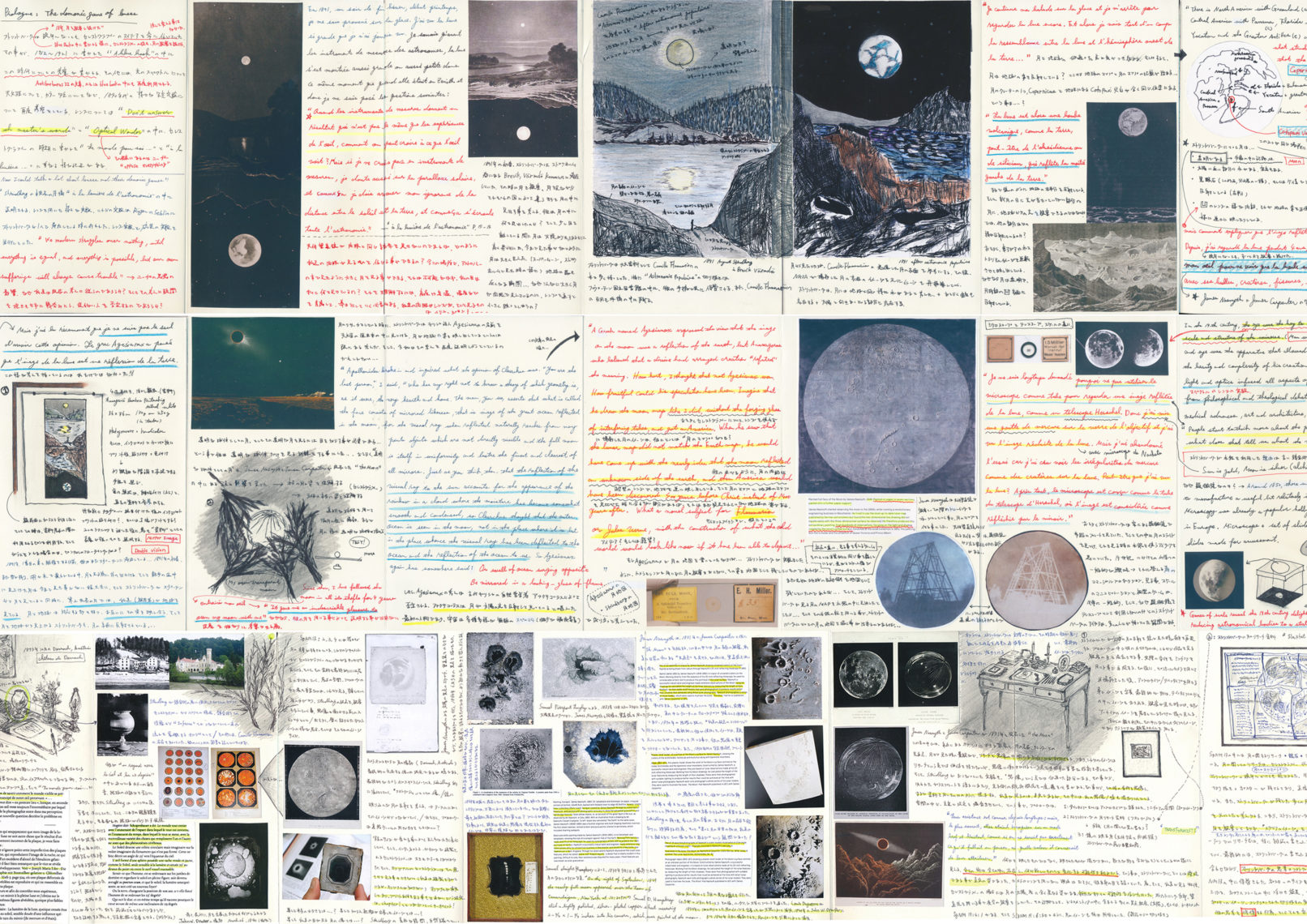

As I have decoded his thousands of research notes, astronomical observation notebooks, clippings and writings from various scientific journals in the archive of the Royal Library of Sweden since 2018, I have begun to understand that the preposterous ideas of the Celestographs were not false conceptions without any basis, but a “philosophy” born of personal reflection and the tendency of the times during which photography became in many ways “the retina of the scientist”, as the French astronomer Jules Janssen said. I also notice that some of his ideas are closely linked to the birth of photography, when the photographic medium was still “ideas and traces”. Now that I’ve been confronted for years with these different fragments of the creative process, I think I can say that his ideas are “false” research results that have no value from the point of view of modern science but are “true” research results from the point of view of the ancient science that seeks the truth of nature in philosophy and contemplation. And just as the history of photography was not made only by the history of photography taught in school, but the various research and traces of proto photographers that existed around the history of photography shaped the “non edited” history of photography, it is misconceptions and chance that have formed the science we know today. That’s why I’m interested in photographic imprints that have disappeared without being established, photographic ideas described in ancient literature or the thought process of the birth of photography. For me, borrowing a phrase from Walter Benjamin’s “A Short History of Photography”, “The fog that covers the beginnings of photography” seems to illuminate the tenuous boundaries between what has been established as history and what has not.

Reflecting these ideas, “Stjernhimmeln (the heavenly sky)” consists of 5 chapters. Each chapter tells a different chronology and reality (alternative facts) around the Celestographs and oscillates between past and present, truth and implausibility, reflecting the historical context in which they were created (the transition from natural science to modern science). Most of the images are camera-less photographs, such as computer-generated images using astronomical software, collages, photograms made from dust and chemical reactions. Each work or fake archive reflects Strindberg’s ideas, translated by my ideas and imagination, from scientific treatises of the time, from Strindberg’s wife Frida Uhl, or from her grandparents Cornelius and Marie Reischl (different perspectives on Celestographs). By combining these “traces of thought” with actual scientific and astronomical photographs, the aim of this project is to construct a “mind map” space and question the notion of representing the “unknown/invisible” in the photographic image. I believe that the questions raised by this project lead viewers to look at photographic images from a new perspective, especially in this age when modified information reaches us on a daily basis due to the popularization of AI-based image processing technologies and social media, which have become a tool for gathering information especially among the younger generations. What can we learn from these “unfixed” images after 131 years?

More information and photos coming soon.

Production supports :

La Capsule – Résidence création photos, Bourget, France

La Cité internationale des Arts, Paris, France

Landskrona Foto, Sweden

Museum der Moderne, Austria

Strindberg Museum Saxen, Austria

Dornach Castle, Austria

Subvention :

Drac Hauts-de-France (aide individuelle à la création 2024)

Exhibition view :

Landskrona Foto, Sweden in 2025

La Capsule – Résidence création photos, Bourget, France in 2019