Burning Ground

2023〜 (on going research)

While researching more than 30 slag heaps (there are over 200) in the mining basins of Nord-Pas-de-Calais during the creation of Chromophore, I discovered that several of them had experienced major fires. This was because some of the accumulated coal continued to burn (combustion), and the fire broke out spontaneously due to summer dry weather and rising temperatures (global warming), or was caused by arson. When I visited these burnt slag heaps one year after the fire, it seemed to me that nature had already created a new environment, even though blackened trees and soil remain in some places. New branches are growing on tree trunks that appear to have died in the fire, dandelion flowers are blooming all around, and lichen is forming new life in the burned fields. Faced with these natural forces of transition, I was reminded of the great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake of 1995, which I experienced at the age of 9.

The streets that existed until yesterday have disappeared, concrete buildings have collapsed, wooden houses have been burned to ashes, and the ground where the fires started still retains its heat. Walking through these surreal and vanished urban landscapes, frightened by the aftershocks, I keenly felt the smallness of human beings in the face of nature. Comparing the city of Kobe, which was rebuilt over a period of about 10 years, with this area, where a new environment was created within a year of the fire, I felt a strong sense of awe toward nature. Thinking about my own culture, which has always been threatened by natural disasters but has sought a form of coexistence with nature, I began to reflect on my own identity. Little by little, what was too ordinary becomes visible… That is why, once again, I am driven by the desire to capture the imprint of time that remains on the site using local materials, drawing inspiration from Japanese papermaking, dyeing, and the production of ancient natural pigments. This project, “Burning Ground,” currently in production, consists of the following two experiments:

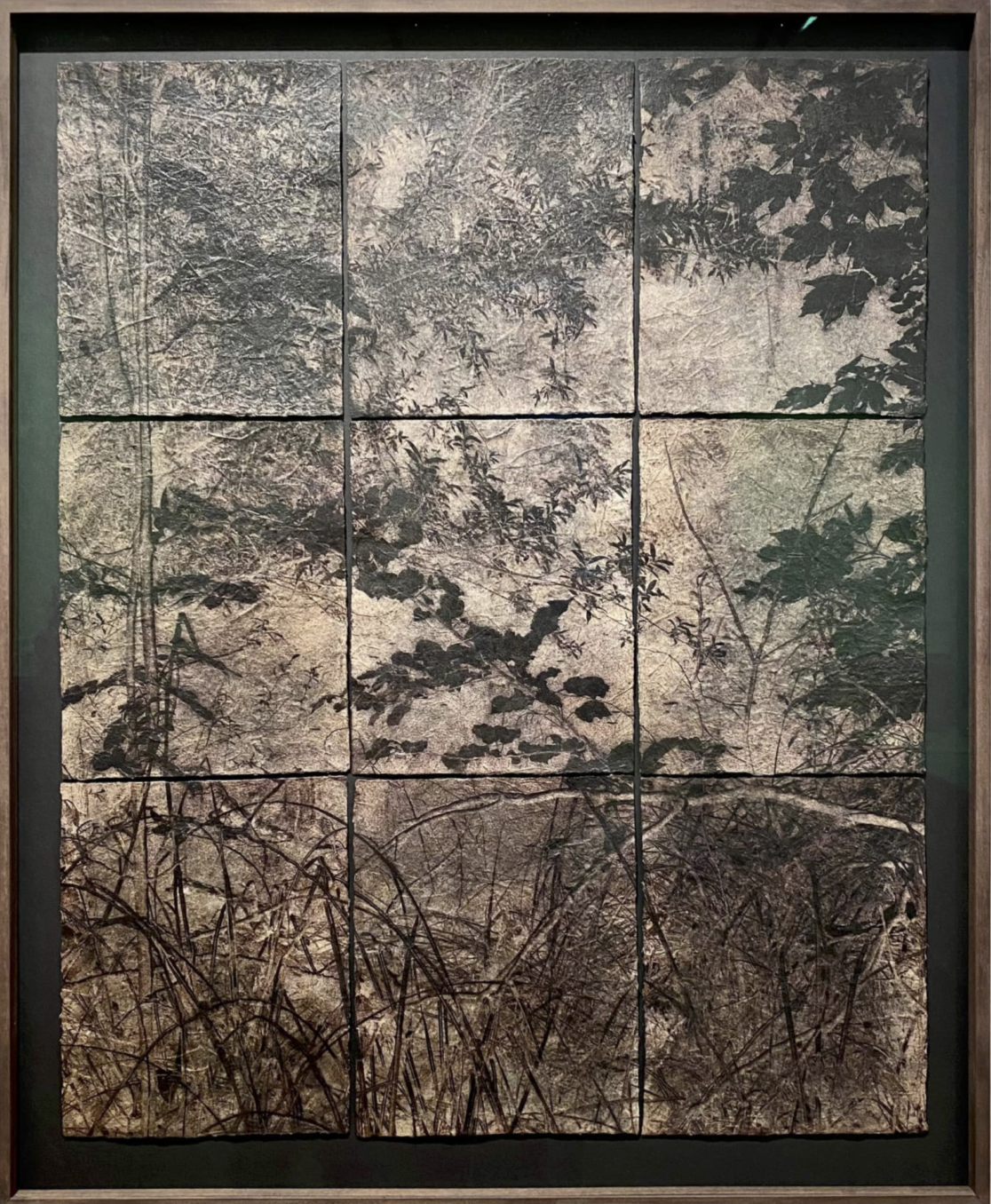

1. Fossil

Visit slag heaps where natural or human-caused fires have occurred and photograph areas where traces of these fires are still visible. Make handmade paper using wild plants photographed or found in the surrounding area, then dye them by hand using black or red shale from the site. After creating pigments from burnt wood soot and crushed coal collected on site, print the image onto tattoo stickers using photopolymer engraving. The photopolymer-engraved image is then transferred onto hand-dyed paper. This complex production process frees the final image from the artist’s control and allows nature to be the driver of creation. Just as the environment in which the images were taken gradually changes and the same “time” can never be achieved, each final image becomes a “fossil” reflecting the time created. For me, soot and charcoal are materials that symbolize the activities of miners as well as evidence of fire.

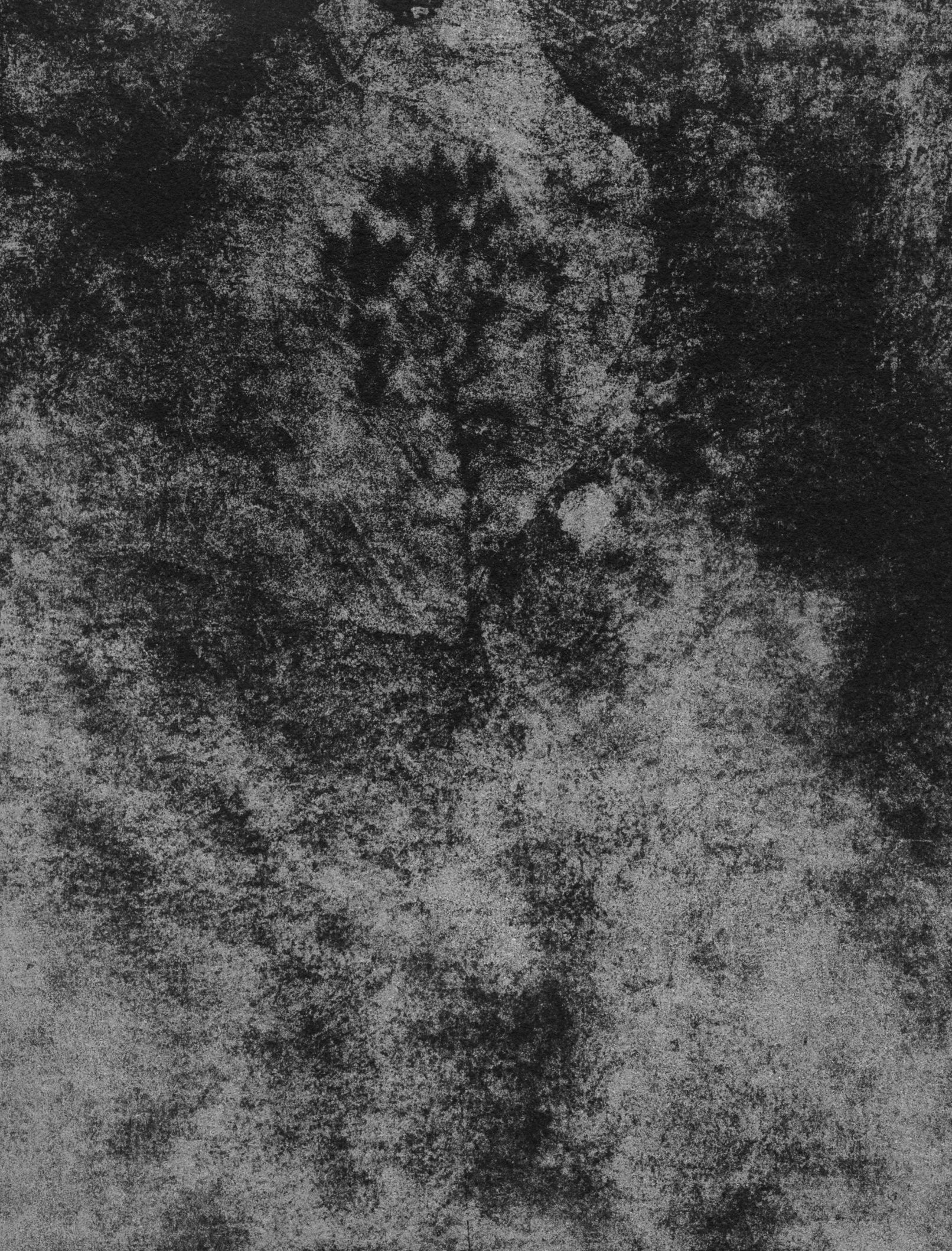

2. Imprint

Visiting burning slag heaps and photographing the wild plants that grow there with a view camera. After developing the negative film, it was buried in the burning soil and left for several months to capture the imprints of heat and chemical reactions on the photographed surface. Finally, these images were printed using a gum bichromate technique, with ash made from wild plants from the site. By freeing the image creation process from the artist’s control, allowing nature and time to dominate the entire production process, the result is a fossil of months of natural activity on the site. For me, ash is a material that symbolizes birth and death, the transitions of all living beings.