Latent

2021 - (ongoing project)

Several archaeological sites are spread throughout Kyoto City, like a collage weaving together the layers of time to the present day. Since many of these ruins are buried underground, archaeological excavations are always conducted as part of any new construction projects. Moreover, in the history of Kyo-yaki (Ceramics produced in Kyoto City) which is essential in talking about the history of Kyoto, progress has been made in archaeological research on the chronology and inscriptions of the pottery, not only due to the improvement of research on literary sources and artifacts, but also due to the successive accumulation of materials from the excavations. However, excavations of the kilns themselves have only recently been undertaken in-depth, so there are still many uncertainties about the history of Kyo-yaki production. In addition to this, archaeological research on post-modern Kyo-yaki is still in its beginning stages.

Kyo-yaki was the general term for ceramics made in various areas of Kyoto city, including Awata-yaki (Awataguchi), Yasaka-yaki (Yasaka), Mizoro-yaki (Mizoro) and Kiyomizu-yaki (Gojozaka), but due to the decline of the pottery industry over time and the Great Depression, only Kiyomizu-yaki survived and was chosen to mean Kyo-yaki. One of the major ceramic production areas in Kyoto, Gojozaka is reputed to be the site where Sousaemon Otowaya opened a kiln around the Otowa River in 1641. Although the kiln was initially called Otowa-yaki using the name of the river, the needs changed and in the 18th century, the kiln was integrated with Kiyomizu-yaki, which was produced in the area of Kiyomizu-zaka, in front of the gate of Kiyomizu temple, in order to develop the business and ensure its survival. As a result, there were more than 20 kilns operating in Gojozaka at the beginning of the 20th century, and it is said that at its peak, the smell of burning pine wood and its smoke was rising every day.

Thus, the Gojozaka area, which had prospered mainly in the production of scientific ceramics and vases for export, gradually began to lose its vitality due to the consequences of World War I and World War II, the evacuation of civilians in 1944, and the difficulty in obtaining materials and the increase in costs. In addition, with the urbanization of Kyoto City in the post-war period, the black smoke from the pine trees which symbolized the commercial prosperity of the area, was now considered as air pollution as more housing was built in the Gojozaka area, which was previously inhabited mainly by technicians and craftsmen working on the climbing kilns. In 1968, the Japanese government promulgated the Air Pollution Control Law in response to the frequent pollution situation causing diseases such as Yokkaichi asthma and Minamata disease, and the traditional kilns were replaced by electric or gas kilns.

Some of the kilns continued to operate by installing smoke control equipment, but continuous protests from the community and the enforcement of the Kyoto Prefecture Pollution Control Ordinance in 1971 forced the shutdown of all kilns. To make matters worse, after a period of strong economic growth, the collapse of the bubble economy, the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers and the lack of workers (the problem of succession of craftsmen’s skills) led to the rapid decline of Gojozaka. Finally, the rise in land prices due to the “revitalization of cities by tourism” had caused the traditional businesses and old lifestyles, which continued to operate despite their financial difficulties, to disappear and be replaced by new business activities such as guest houses and hotels for tourists. The climbing kilns in Gojozaka, which had a history of more than 100 years, were demolished one after another due to the construction of tourist accommodations without recognition of their heritage value, and only four kilns (Fujihira, Kanjiro Kawai, Bunsai Ogawa, and Dosen Irie) have miraculously survived. The four remaining kilns are currently in constant danger of being demolished. As evidence, the site of the former Dosen Chemical kiln was demolished for the construction of a hotel in 2019, and part of the Bunsai Ogawa kiln collapsed in 2018 due to vibrations from nearby demolition work. Gojozaka, once a prosperous “pottery district,” has been transformed into a “hotel district” by the rapid increase in tourist traffic since 2012, and is now overflowing with newly built stores aimed mainly at foreign tourists. On the other hand, the gradual disappearance of Kyoto’s traditional streets has led to a decline in the number of Japanese tourists. Many accommodations and souvenir stores are currently closing due to the decline in the number of foreign tourists due to the COVID-19 since February 2020. And if foreign tourists do not return once the situation is resolved, many empty properties will be created around Gojozaka and the area will become a ghost town. And even if the tourists come back, the old Gojozaka will never come back.

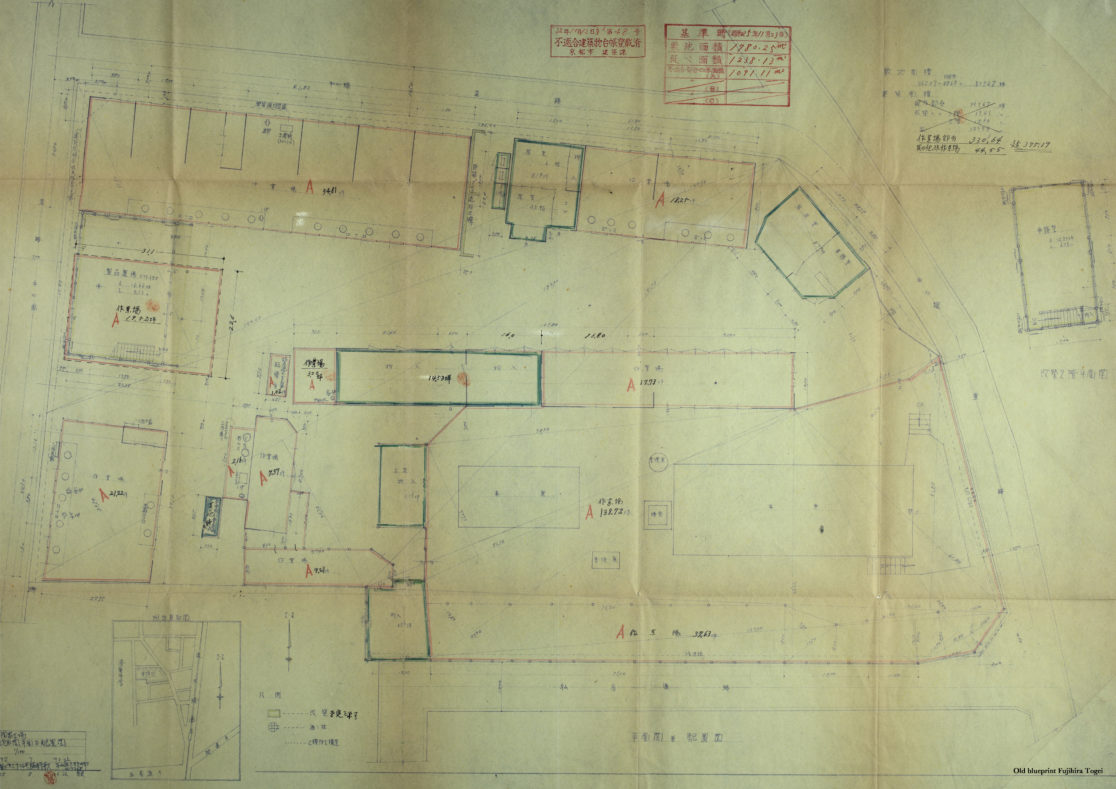

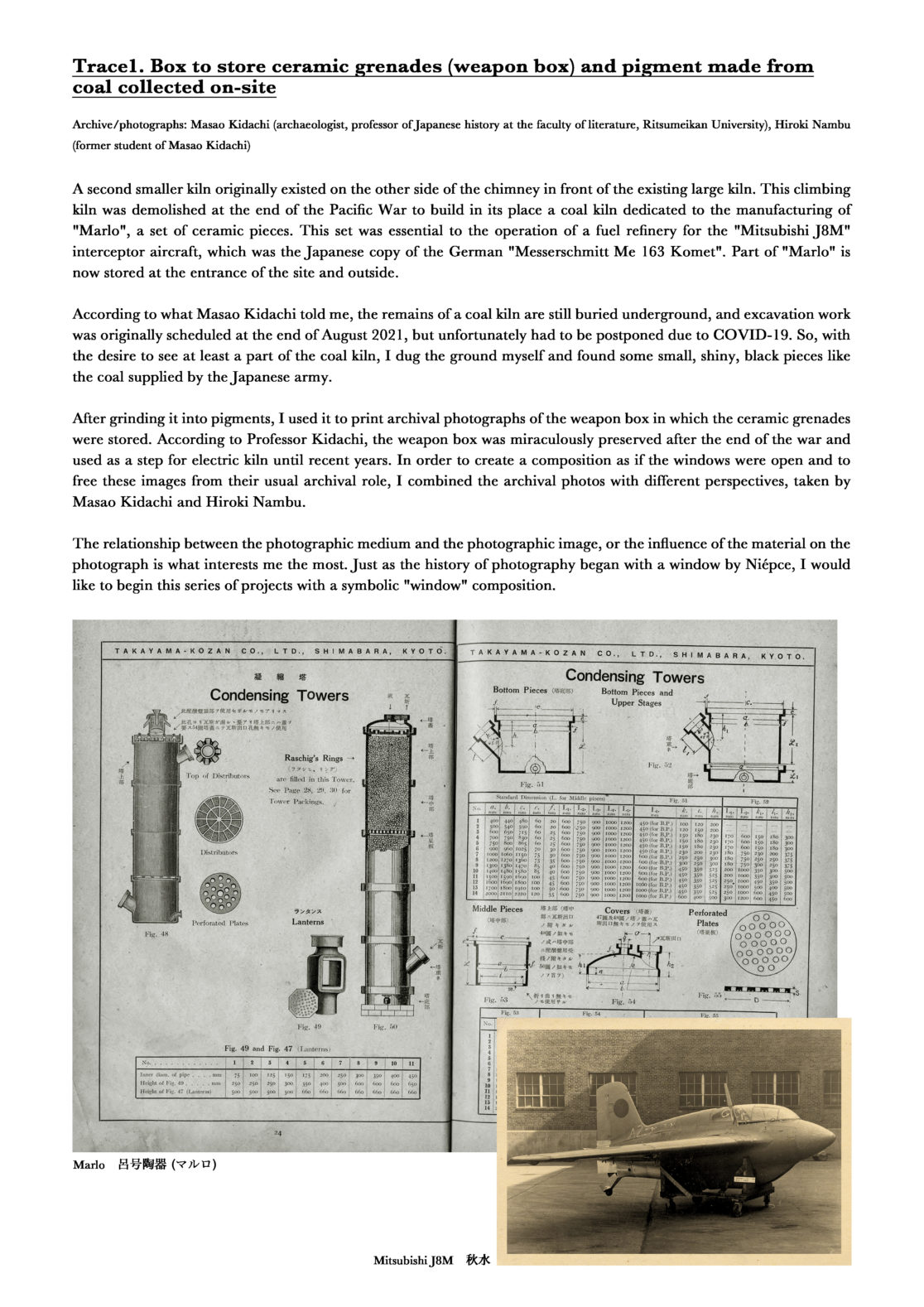

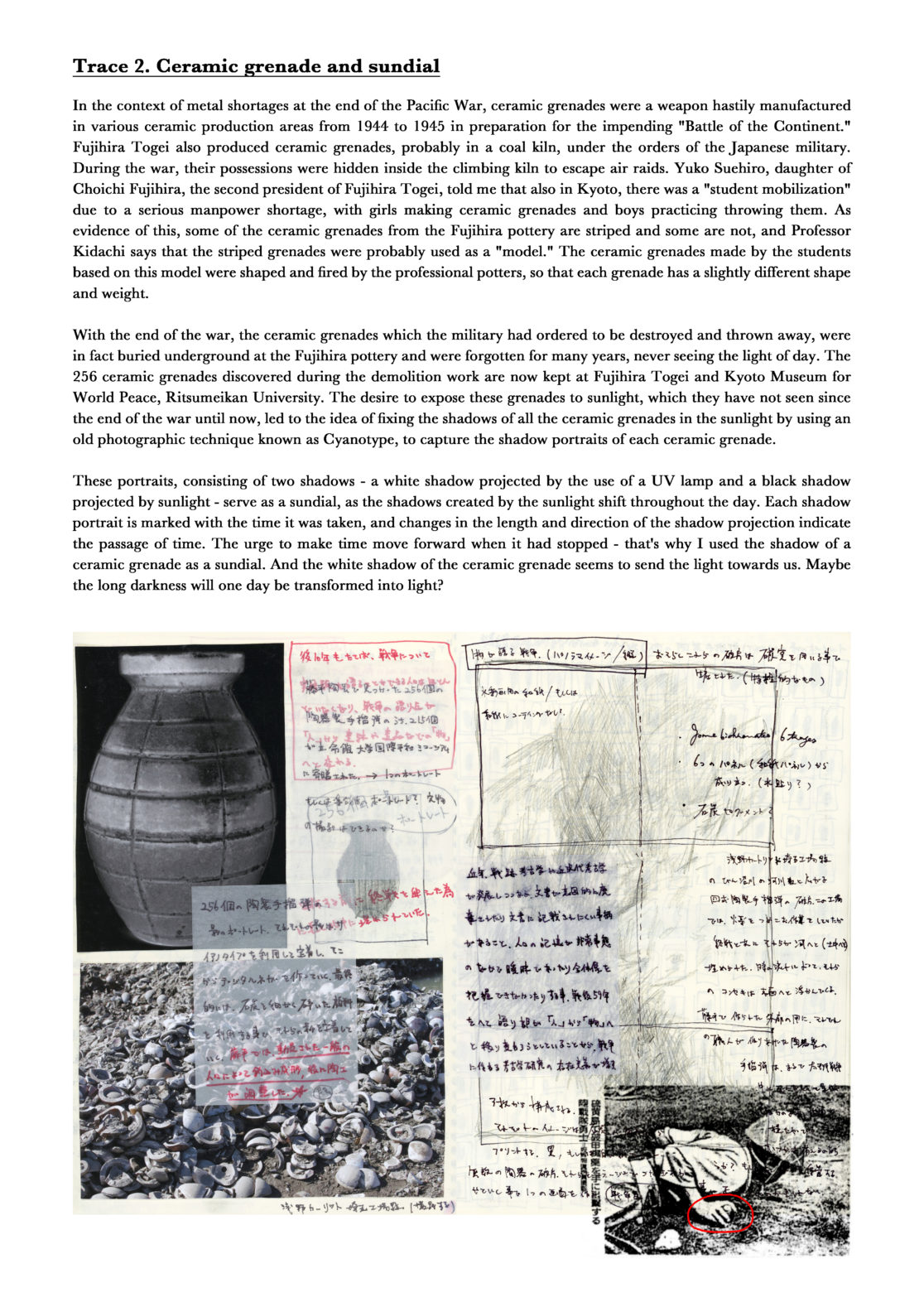

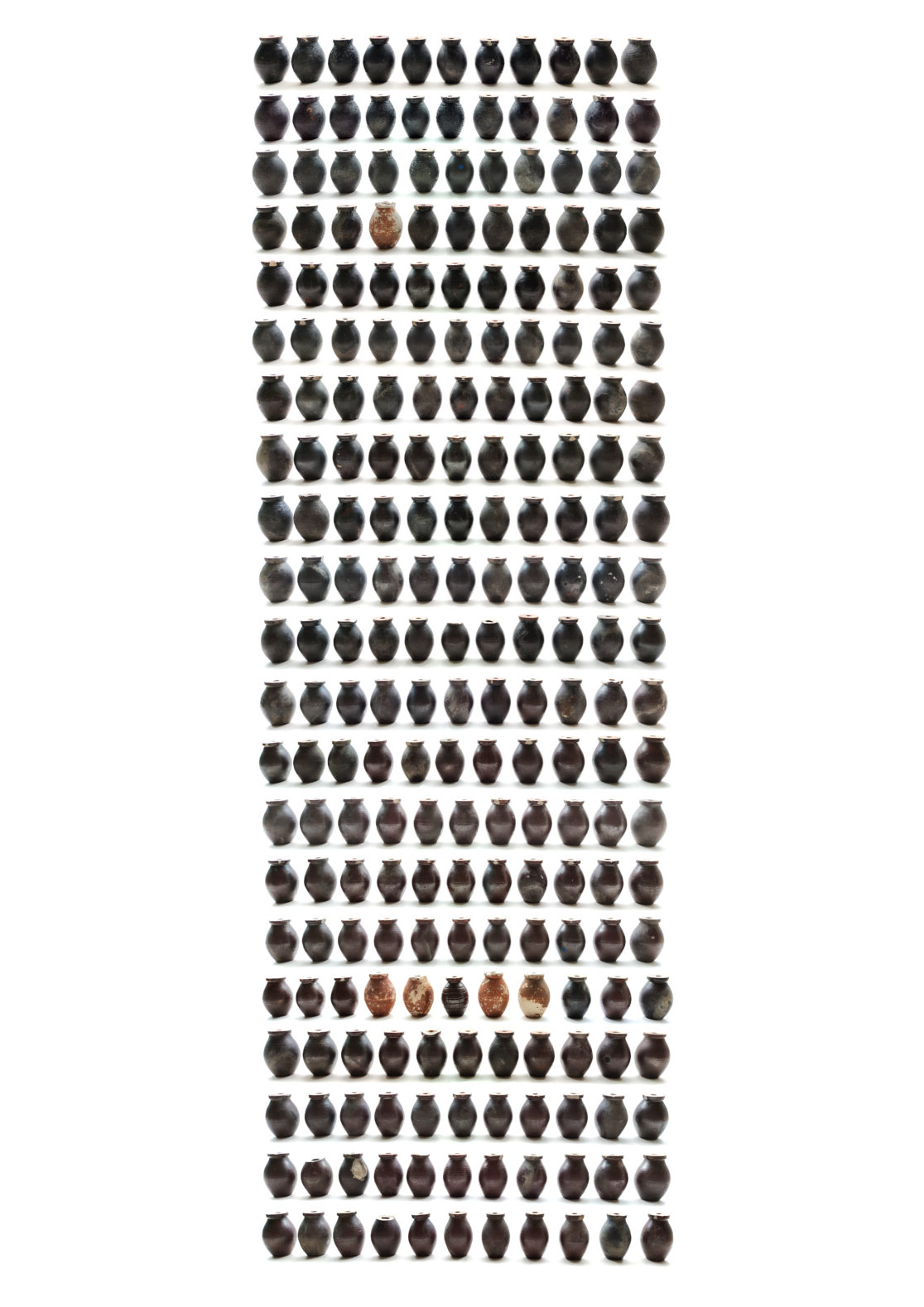

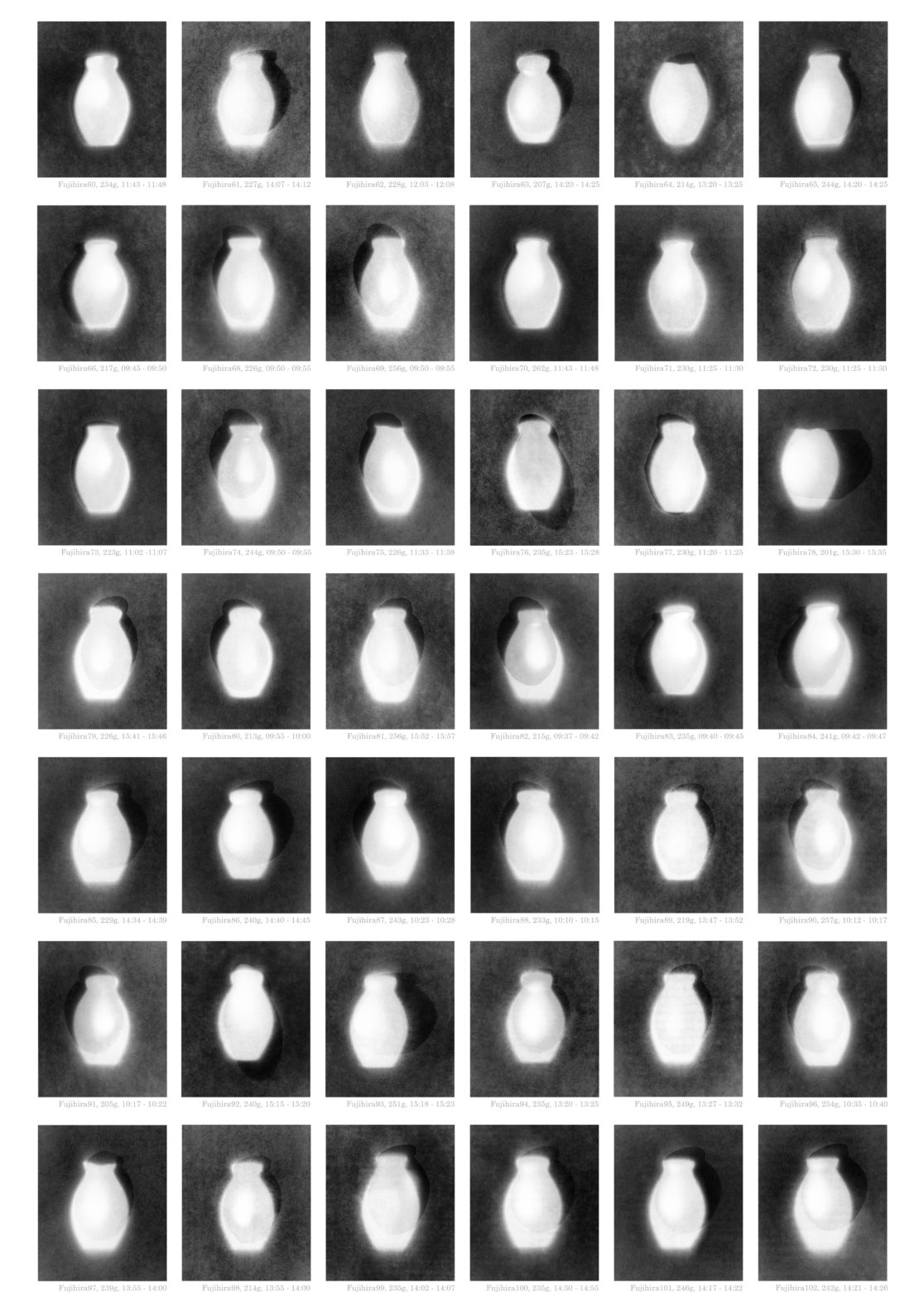

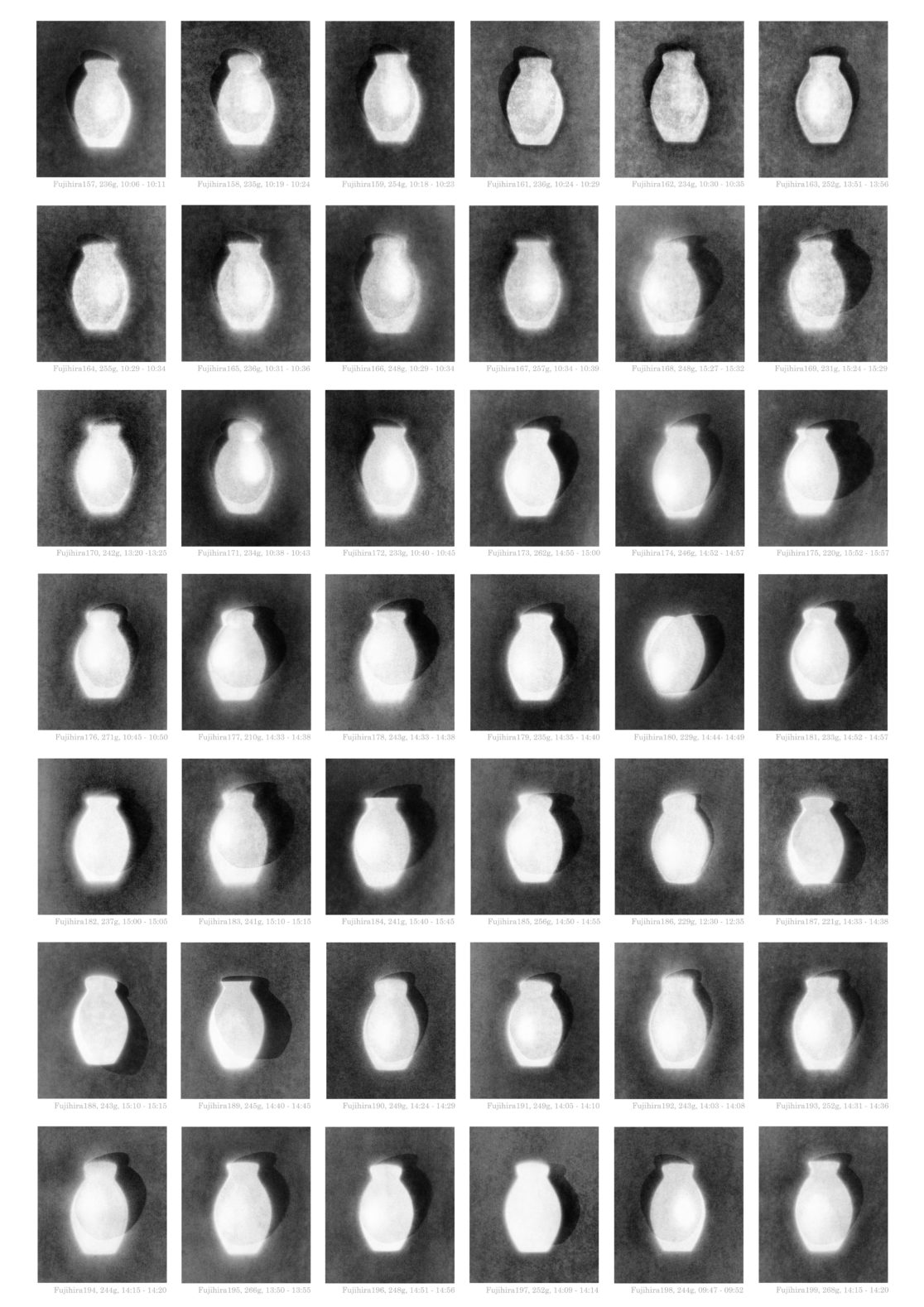

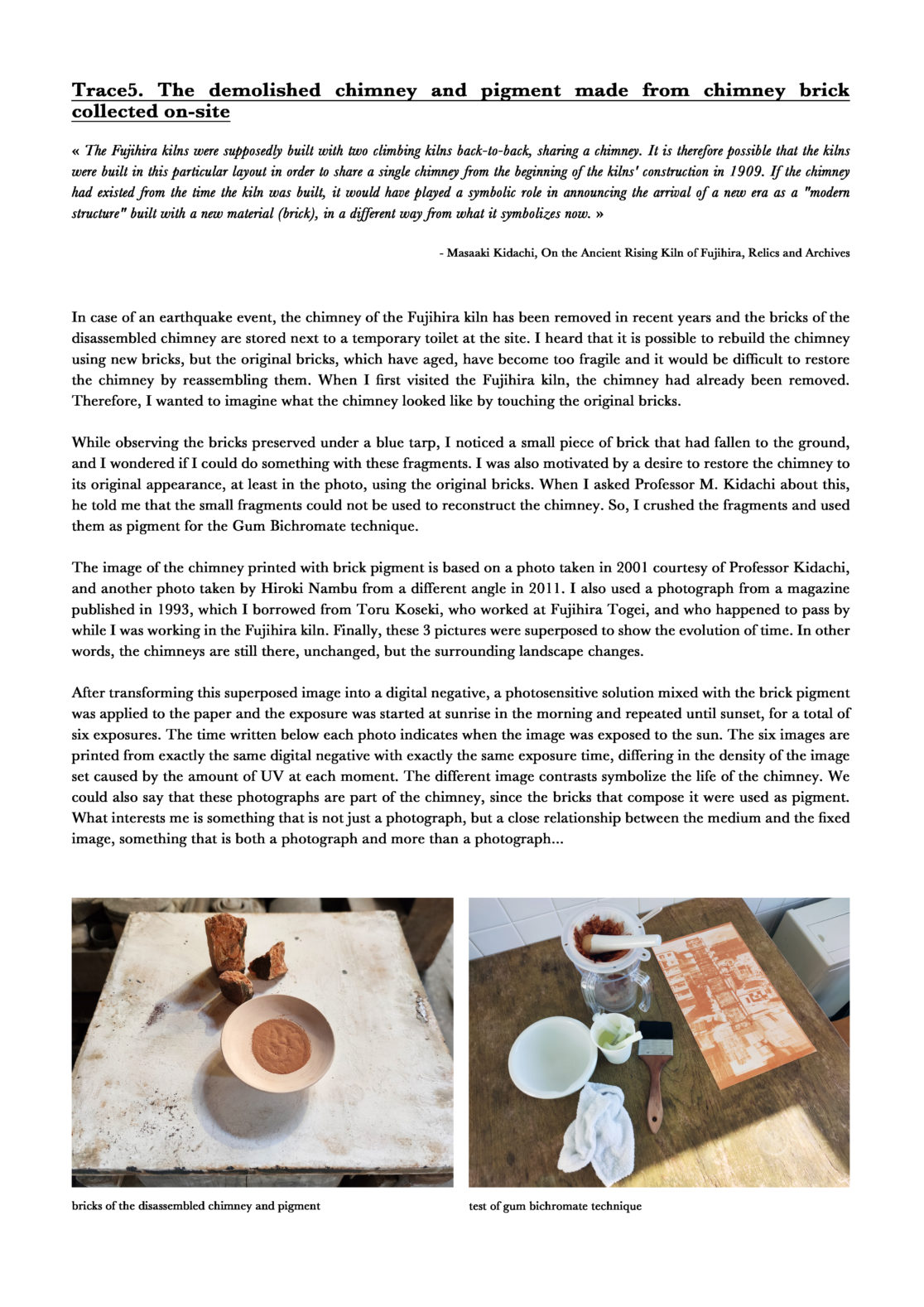

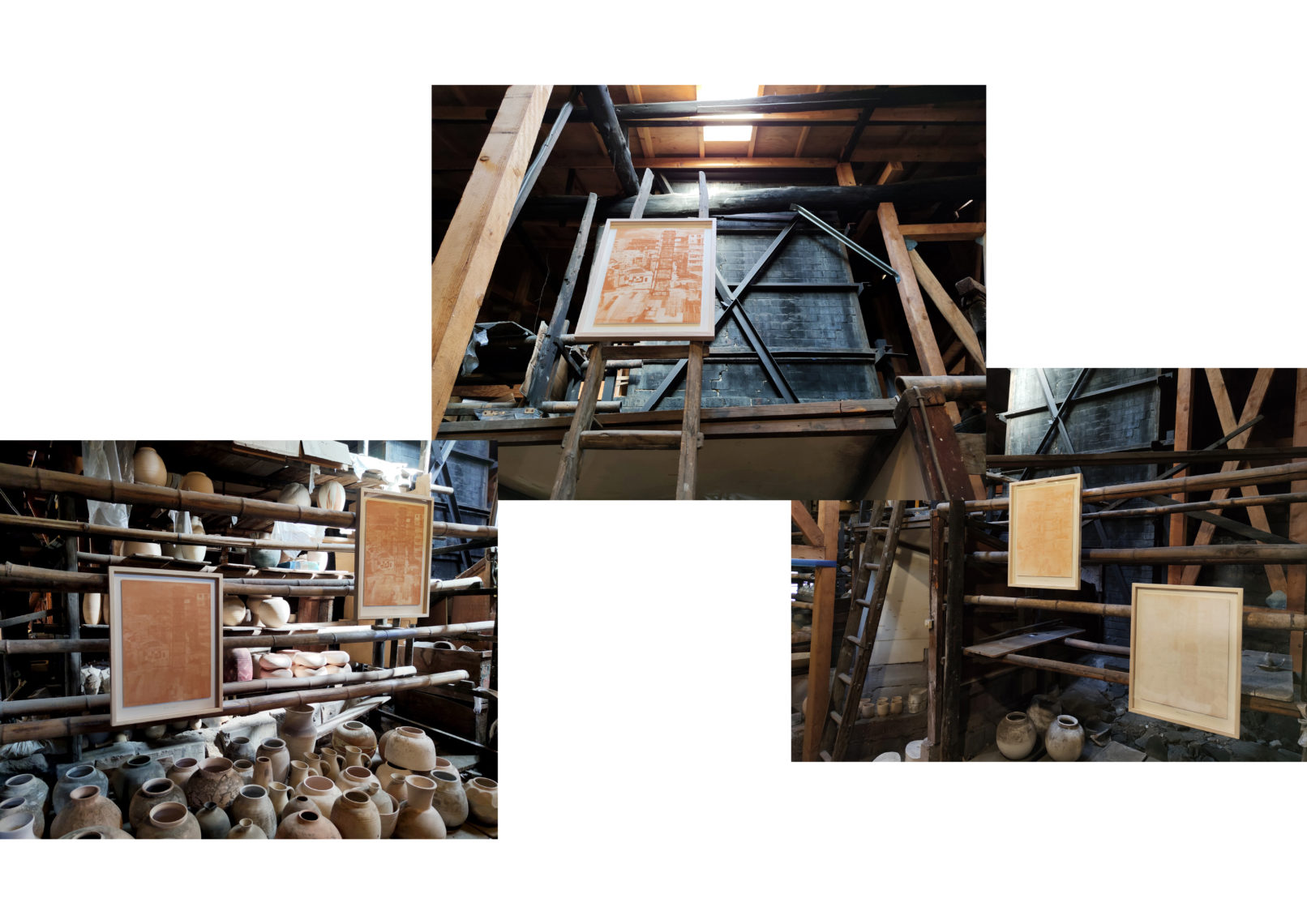

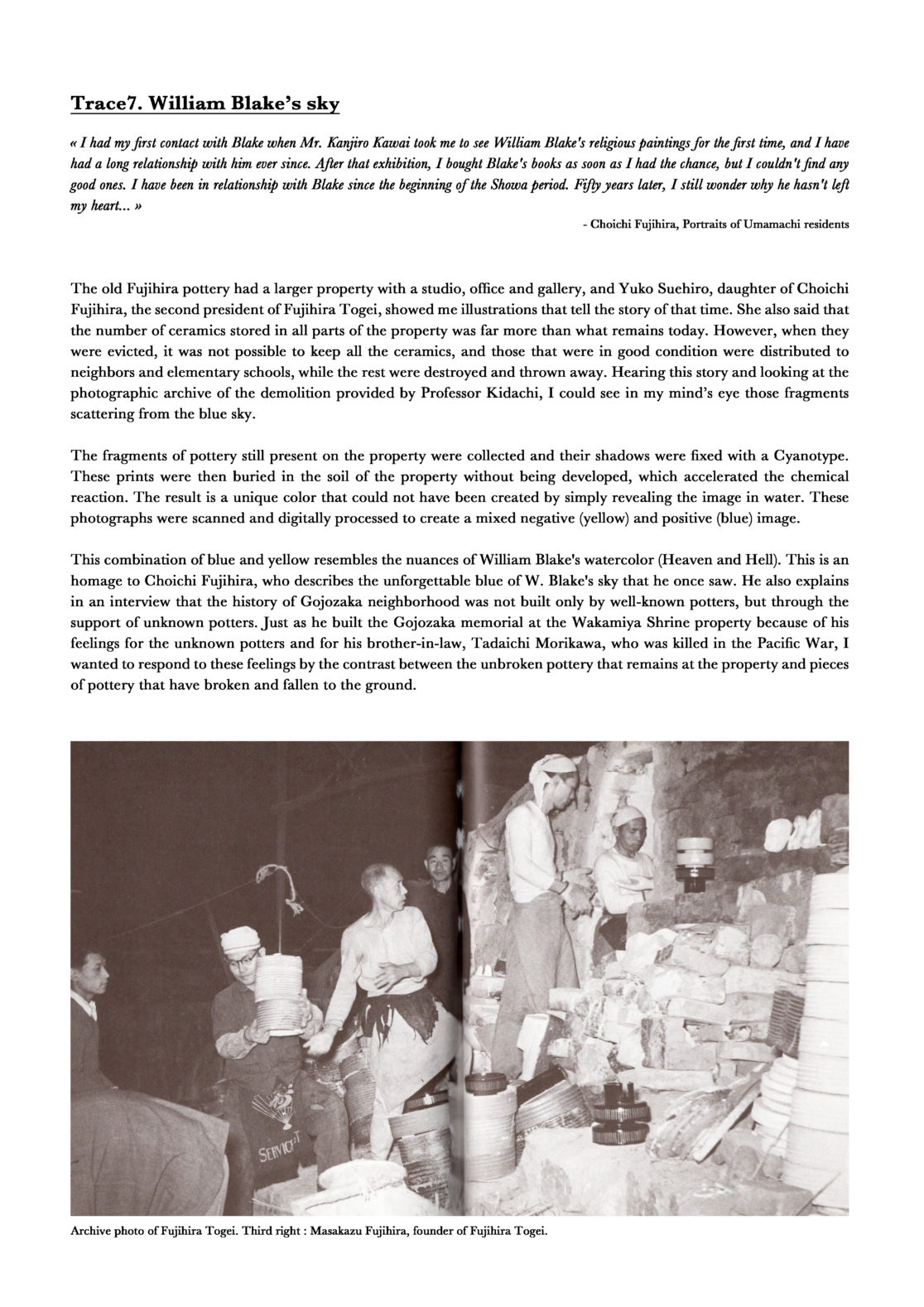

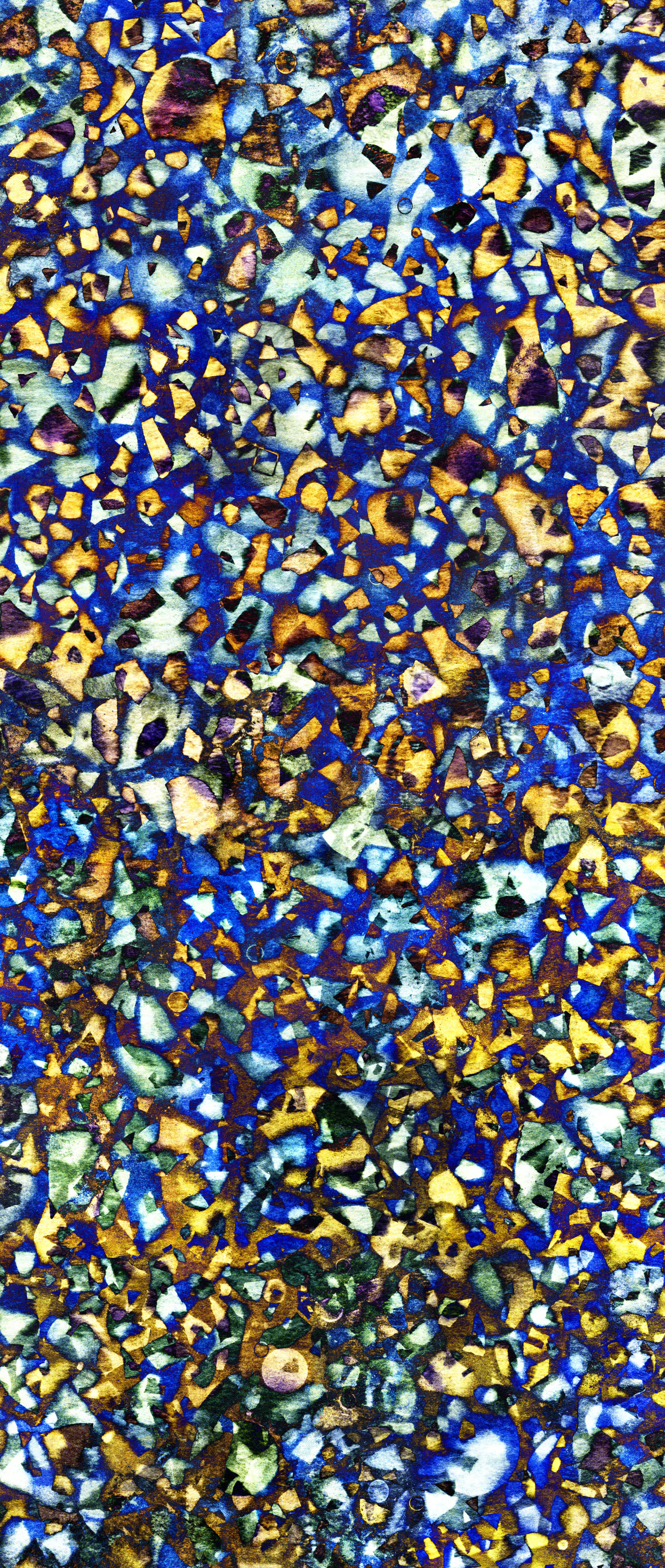

The only one among the 4 remaining upright kilns in Gojozaka that has remained nearly unchanged since the time of its operation, the Fujihira Pottery Kiln is a precious industrial heritage site built in June 1909 by the Kyoto Ceramic Joint-Stock Company. This kiln has the largest scale in Kyoto City, and was once built vertically in two parts, one large and one small, to produce large quantities of pottery for export. Fujihira Togei Limited, the owner of this kiln until 2008, was founded in 1916 as “Fujihira Seitôjyo” in Umamachi, near Gojozaka. In the early years of the company’s existence, production was carried out by renting a kiln, and it was in 1943 that the company purchased a climbing kiln from the Kyoto Ceramic Joint-Stock Company. Even during wartime, when strict material controls were imposed, they built a coal-fired kiln by demolishing a small wood-fired kiln, to produce ceramic grenades, scientific ceramics and rocket fuel refining equipment. After the war, while making “Mingei” (Japanese art movement, inspired by the English Arts & Crafts movement) under the leadership of Takekazu Kawai and Kanjiro Kawai, the company continued to produce scientific ceramics. However, the business gradually declined due to the emergence of new large-scale scientific ceramics production areas, competition from “Mingei” nationwide, and changing needs of the time. Finally, in 2008, the land was sold to Kyoto City as a school site and demolition work began to clear the property. Afterwards, the demolition work was cancelled, and the city of Kyoto decided to preserve the kiln, thanks to the active demonstration of people such as Naomichi Suehiro, third president of Fujihira Togei, the association for the preservation and use of the rising kilns and Masao Kidachi, professor at the faculty of literature of Ritsumeikan University. Today, only the structure containing the climbing kiln, known as “Yakiba,” remains on the site, the former studio area has become a parking lot for elementary school staff, and the 350-year-old Chinese hackberry tree died because it was uprooted and moved to allow for demolition work. In addition to that, the chimney of the rising kiln was cut in case of a seismic event and new supports were installed in the “Yakiba” to strengthen the building, which caused the original appearance of the property to disappear. Facing this place, it seems to me to symbolize the suffering that takes place in Gojozaka. Each part has been cut, over repaired, and the building remains alone, as if it has been forgotten, without a clear answer to the question of its survival or its demolition…

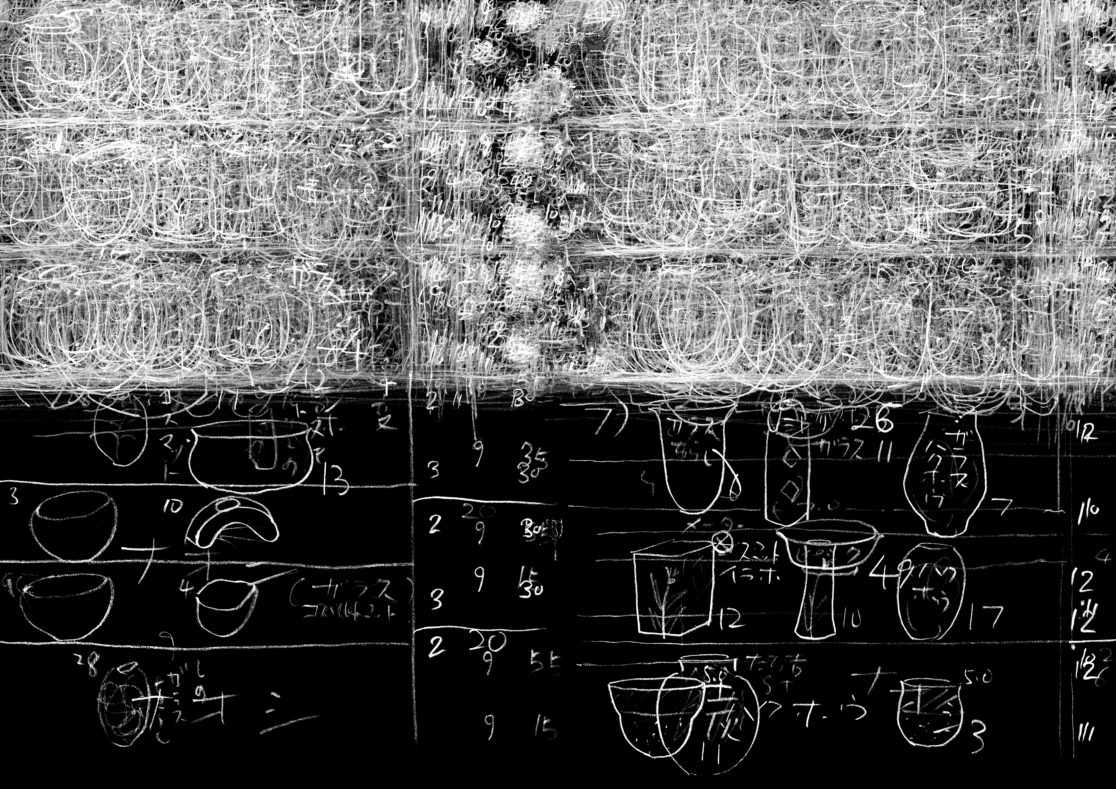

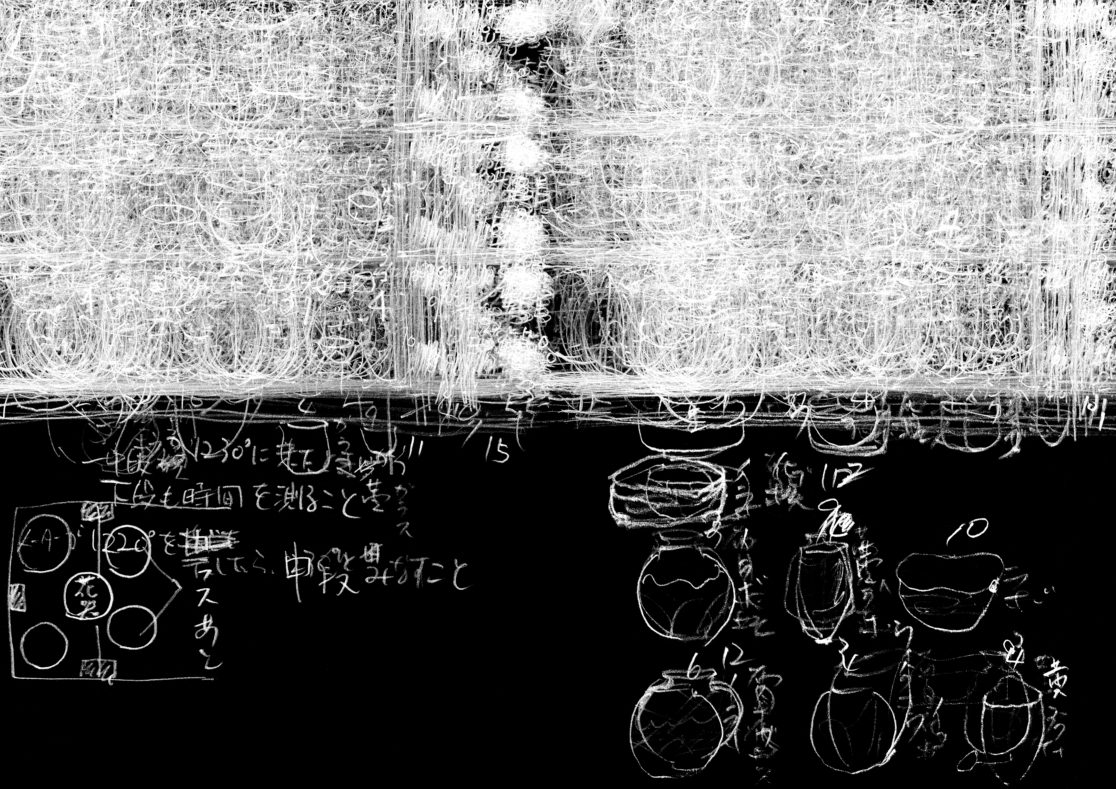

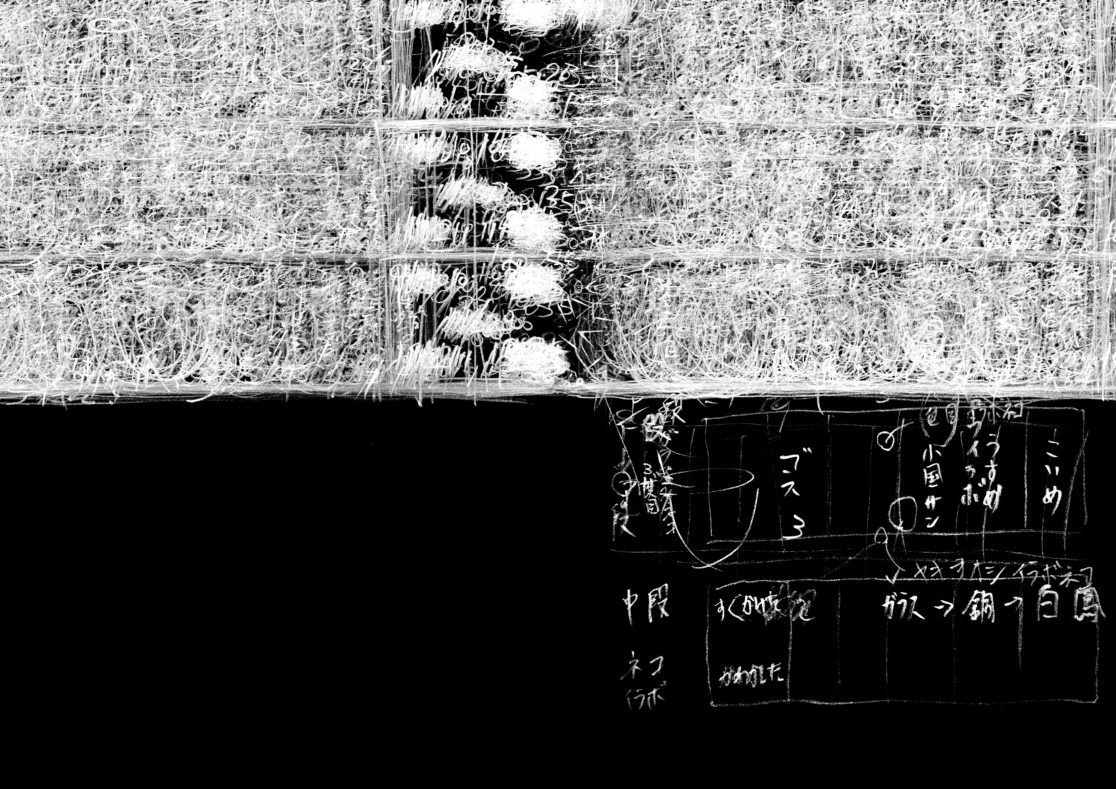

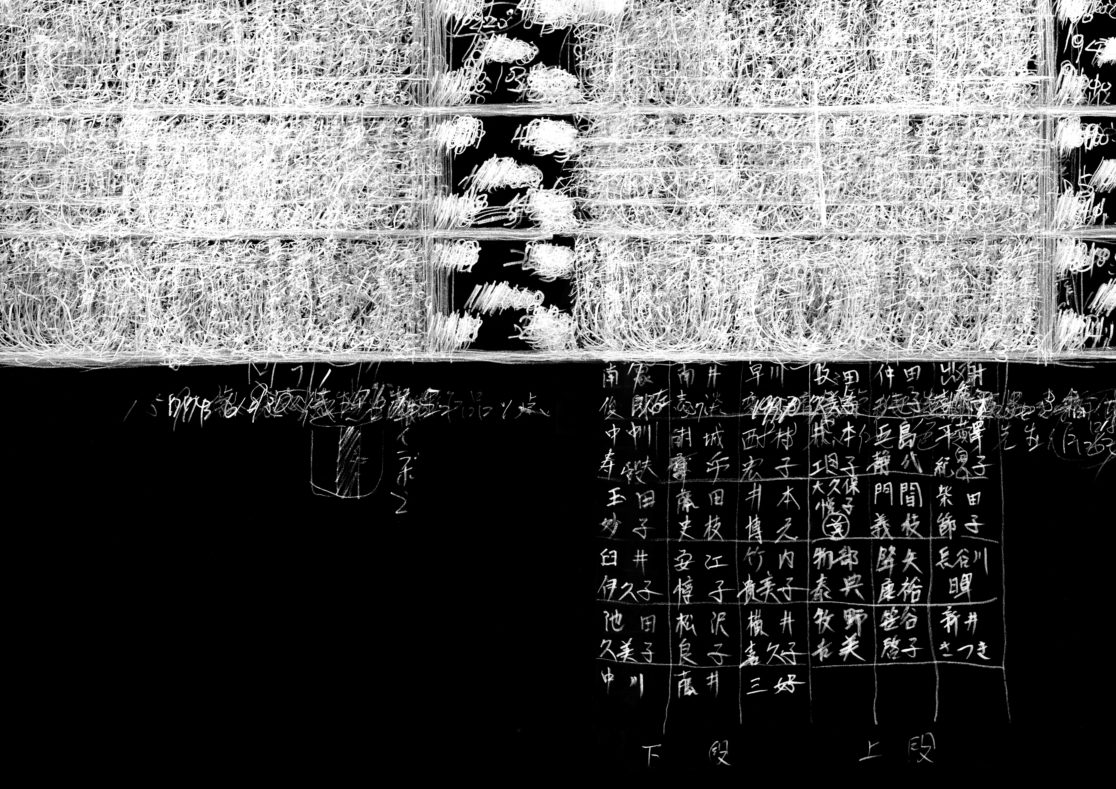

The Japanese Tourism Agency, established in Japan in 2008 in response to the decline of local towns, has created a major conflict between locals and tourists caused by problems of noise and illegal dumping of garbage, by promoting a development that favors tourists. In addition, the increase in demand for land led to a significant increase in land prices, causing residents to leave the area. This meant the end of the community’s history built by the locals. The transition to electric kilns after the closure of the climbing kilns in 1968 resulted in the loss of the community around the kiln and led to their eventual isolation. Among the more than 20 kilns originally located on Gojozaka, many were shared as rental kilns, and potters who did not have their own kilns brought their works once or twice a month for firing. Not only potters, but also woodchoppers, fire-starters, and other specialized groups were formed, taking turns to watch the fire for three days and three nights. The conversations that accompanied them were also an important exchange of information and the key to building a sense of community among the locals of Gojozaka. And because they did not perform all the processes themselves but delegated them to others, for many potters, the firing was an “act of prayer” symbolizing the feelings of all involved at the kiln. However, since the transition to electric kilns, ceramic art has become an autonomous form, where the entire process is carried out by the individual, and because there are fewer errors during firing, it has gone from an “act of prayer” to “one of the processes” and the dialogue of residents and technicians that used to exist has also disappeared.

This trend is not only in Gojozaka, but also in the modern societies of all countries, which are more and more individualized. In various industries, the development of technology has increased convenience and productivity. The use of machines has been a major positive economic factor, because similar products can be mass produced. On the other hand, we have not only lost the ability to see the foundations of “things”, but also the ability to find answers through trial and error, dialogue with others, and mutual understanding, which has led to the degeneration of our spirit. That is why when I talk about the climbing kilns and the old Gojozaka district, it is not out of nostalgia for the good old days, but to express a warning to our modern society. What can the 4 remaining kilns of Gojozaka tell us today in the face of social problems in Japan such as depopulation in the countryside and solitary deaths, which are getting worse every year? How can we address the past as a current, real problem? What have we gained and lost by prioritizing profit? In the post-COVID-19 era, it is necessary to rethink for whom and for what, community development through art and cultural assets should be used.

In any narrative of memories, there is no single truth, and it is the gaps in memory and the different perspectives that reconstruct and update memories. Even when talking about the climbing kilns, those who were involved in the kiln industry and those who were not, those who owned a kiln and those who did not, those who suffered smoke pollution and those who did not, have very different feelings about this place. The project aims to examine these various aspects that may be perceived as “noise” and to value the time of confrontation with the remaining documents and objects, as well as the conversation with the witnesses of the past Gojozaka. Rather than trying to gather them in one form, the idea is to create an environment where new dialogues can exist between those who know the place and those who do not, by making the different “traces of encounters” resonate with the place so that it tells its own story. The objective of this project is not to recreate the universal memory of a place, but to highlight the memory of the present through the act of carefully following different “traces”, going back and forth between the present and the past, the real and the absent, the defined and the undefined.

Production supports :

MUZ ART PRODUCE

Institut français du Japon – Kansai

Le Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains

EMON,Inc.

Kyoto Prefectural Board of Education

Fujihira Pottery

Ritsumeikan University

Kyoto Museum for World Peace, Ritsumeikan University

Kyoto Seika University

Kyoto University of the Arts

Villa Kujoyama

Fondation Bettencourt Schueller

DMG MORI Co.,Ltd.

KUJIME/ KYORITSU Dr’s LAB. Inc.

by 164 PARIS/Lou Lou Co.Ltd.

Subsidy :

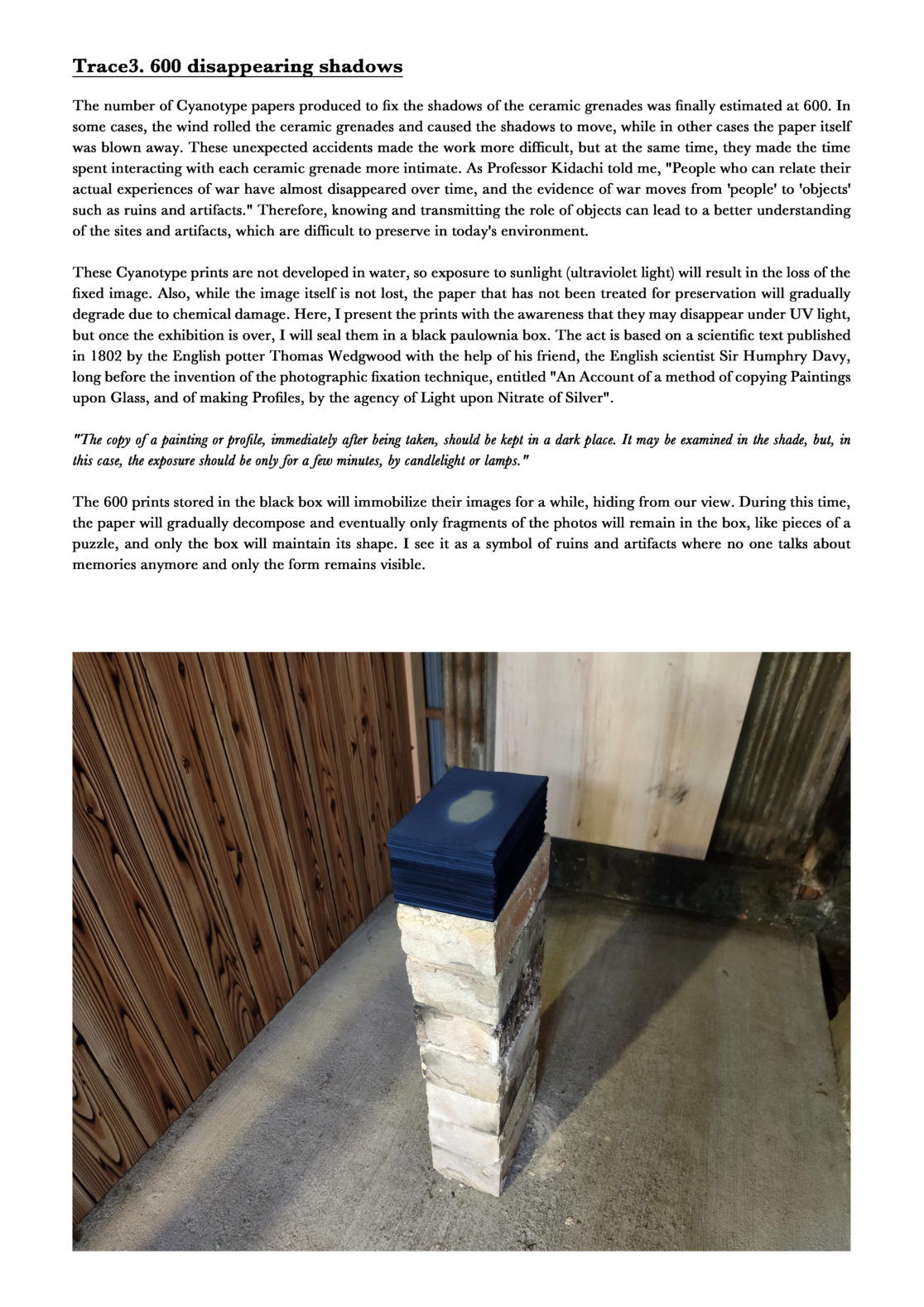

“ARTS for the future!” from the Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan